Liver Cancer Immunotherapy Response Estimator

Estimated Immunotherapy Response Rate

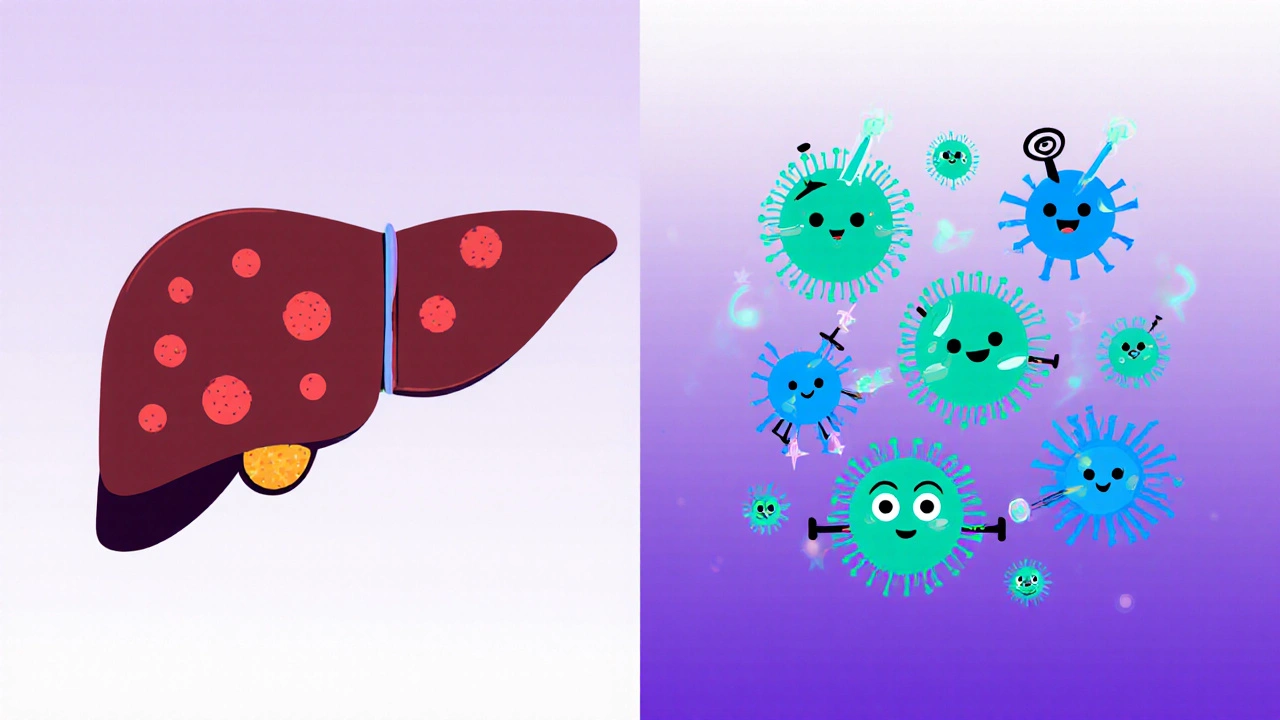

When you hear the words liver cancer and immune system together, it sounds like a science‑fiction plot, but the reality is far more urgent. Over the past decade, researchers have uncovered a tangled dance between malignant liver cells and the body’s defense forces. Understanding that relationship isn’t just academic - it determines which drugs work, who benefits most, and where the next breakthroughs will emerge.

What Is Liver Cancer? A Quick Snapshot

Liver Cancer is a malignant disease that originates in the liver’s functional cells. The most common form, accounting for about 75 % of cases, is Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In 2024, the World Health Organization estimated roughly 905,000 new liver‑cancer diagnoses worldwide, making it the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death.

Risk factors are well‑established: chronic hepatitis B or C infection, long‑standing alcohol abuse, non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease, and cirrhosis. Because the liver is a metabolic hub and a filter for blood, it’s constantly exposed to toxins, which can trigger DNA damage and malignant transformation.

The Immune System’s Role in Cancer Surveillance

Our immune system constantly patrols for abnormal cells. T cells, especially cytotoxic CD8⁺ T lymphocytes, scan tissue for strange protein fragments (antigens). When they spot a rogue cell, they release perforin and granzymes to induce apoptosis. Natural killer (NK) cells provide a rapid, non‑specific response, especially against cells that have reduced MHC‑I expression.

In a healthy liver, immune tolerance is a double‑edged sword. The organ must tolerate food antigens and gut‑derived bacteria, so it maintains a baseline anti‑inflammatory environment. This tolerance, however, can be hijacked by tumor cells to slip under the radar.

How Liver Cancer Escapes Immune Detection

HCC has mastered several tricks to avoid destruction:

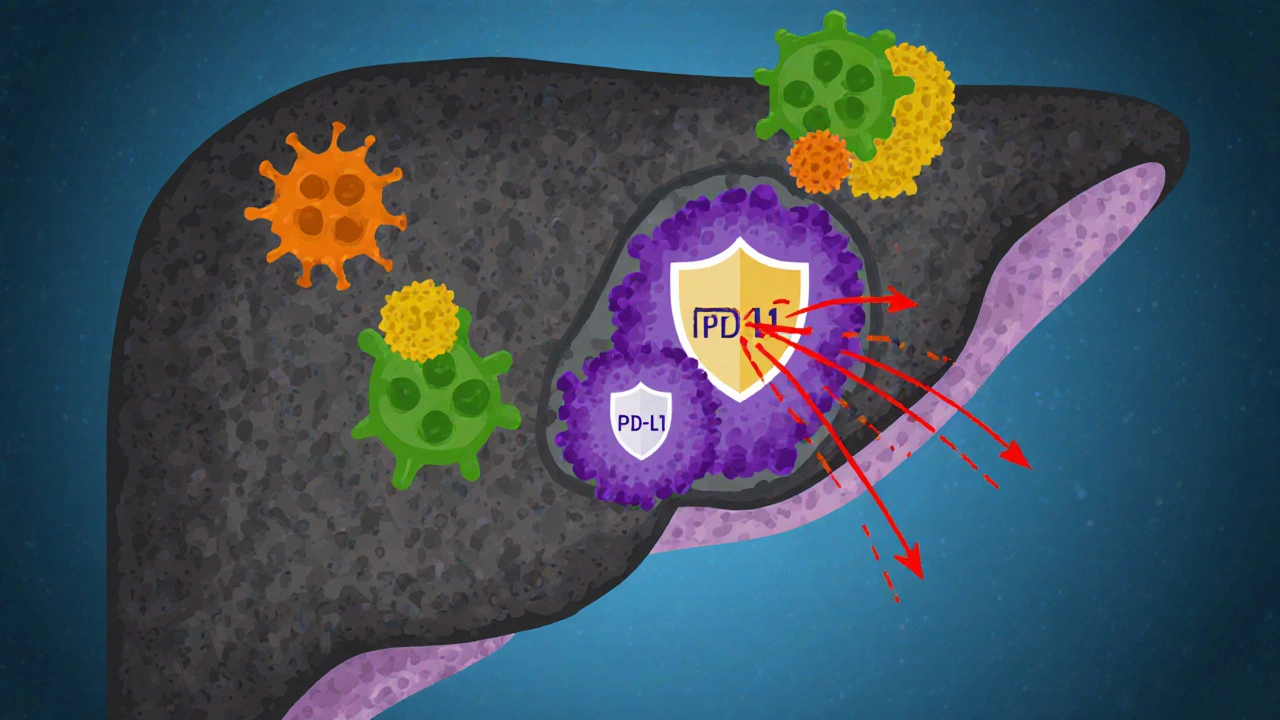

- Checkpoint molecule up‑regulation: Tumor cells often overexpress PD‑1/PD‑L1, binding to receptors on T cells and turning them off.

- Secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines: Transforming growth factor‑β (TGF‑β) and interleukin‑10 (IL‑10) dampen the activity of both T cells and NK cells.

- Recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs): These cells actively suppress anti‑tumor responses, creating a protective shield around the tumor.

- Altered antigen presentation: Mutations in the antigen‑processing machinery lower the visibility of tumor antigens on MHC molecules.

All these mechanisms reshape the tumor microenvironment (TME) into a hostile zone for immune attackers.

The Tumor Microenvironment (TME): The Battlefield Within the Liver

The TME isn’t just cancer cells; it includes fibroblasts, endothelial cells, immune infiltrates, and the extracellular matrix. In HCC, the TME is typically rich in myeloid‑derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor‑associated macrophages (TAMs) that release growth factors and further suppress immunity.

One striking feature is the “fibrotic niche.” Chronic liver disease often leads to scar tissue, and this fibrotic matrix serves as a scaffold where cancer cells hide and receive survival signals. Imaging studies in 2023 showed that patients with a dense fibrotic TME responded 30 % less to standard checkpoint‑inhibitor therapy compared with those having a more “inflamed” microenvironment.

Immunotherapy Options: Turning the Tide

Because the immune system can be re‑educated, several therapeutic strategies have entered clinical practice.

| Approach | Mechanism | Approved Indications (2025) | Typical Response Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Checkpoint Inhibitors | Block PD‑1/PD‑L1 or CTLA‑4 to release T‑cell brakes | Advanced HCC after sorafenib (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) | 15‑25 % |

| CAR T‑cell Therapy | Engineer patient’s T cells to target GPC3 or AFP antigens | Phase II trials; not yet FDA‑approved for HCC | 30‑40 % (early‑phase) |

| Cancer Vaccines | Introduce tumor‑associated antigens to prime immune system | Investigational (e.g., MVA‑AFP) | 8‑12 % |

Checkpoint inhibitors have become the cornerstone of first‑line systemic therapy for advanced HCC, especially when combined with anti‑angiogenic agents like bevacizumab. The landmark IMbrave150 trial (2020) showed a median overall survival of 19.2 months with atezolizumab‑bevacizumab versus 13.4 months with sorafenib.

CAR T‑cell therapy is still experimental for liver cancer, but recent 2024 data from a multicenter Chinese trial using GPC3‑directed CAR T cells reported a 38 % disease‑control rate and manageable cytokine‑release syndrome. Researchers are tweaking costimulatory domains (e.g., 4‑1BB) to improve persistence.

Cancer vaccines, such as the Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vector delivering AFP, aim to educate the immune system before the tumor grows too large. Early studies suggest that vaccine‑plus‑checkpoint blockade may raise response rates to the mid‑20s.

Clinical Evidence: What the Numbers Say in 2025

In the past two years, combination regimens have dominated the headlines. The HIMALAYA trial (2023) compared tremelimumab‑durvalumab (dual checkpoint blockade) against sorafenib, achieving a 2‑year survival of 44 % versus 33 %.

Real‑world registries in Europe and Asia reveal that patients with underlying hepatitis B tend to respond slightly better to PD‑1 inhibitors, possibly because of higher mutational burden from viral integration.

Importantly, biomarker testing is gaining traction. High PD‑L1 expression (>10 %) and an “inflamed” TME (elevated CD8⁺ T‑cell infiltrate) correlate with a 1.5‑fold increase in objective response.

Practical Takeaways for Patients and Caregivers

- Know your liver health: Regular ultrasound and alpha‑fetoprotein (AFP) screening for at‑risk individuals (HBV/HCV carriers, cirrhosis) can catch HCC at an early stage when curative options exist.

- Ask about immunotherapy: If your tumor is advanced, discuss checkpoint‑inhibitor combinations. Many oncologists now order PD‑L1 IHC and T‑cell infiltration panels to personalize therapy.

- Watch for side effects: Immune‑related adverse events (colitis, hepatitis, thyroiditis) can appear weeks after the first dose. Early reporting to your care team is crucial.

- Consider clinical trials: With rapid innovations, enrolling in a trial (e.g., CAR T‑cell, vaccine‑plus‑PD‑1) can provide access to cutting‑edge treatments.

- Lifestyle support: Maintain a balanced diet, avoid alcohol, and manage comorbidities like diabetes to keep your liver and immune system in the best shape possible.

Future Directions: Where Is the Research Headed?

Scientists are exploring three hot avenues:

- Bispecific antibodies: Molecules that bind both a tumor antigen (e.g., GPC3) and CD3 on T cells, forcing a direct attack.

- Microbiome modulation: Early trials suggest that gut‑derived short‑chain fatty acids can boost the efficacy of PD‑1 blockers in HCC.

- Personalized neo‑antigen vaccines: Using next‑generation sequencing to identify patient‑specific tumor mutations and create tailor‑made vaccines.

By 2030, the hope is that a combination of checkpoint inhibition, targeted immunotherapy, and lifestyle interventions will shift the 5‑year survival for advanced HCC from the current < 15 % to above 30 %.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can liver cancer be prevented?

Vaccination against hepatitis B, safe sex practices, avoiding excessive alcohol, and managing metabolic syndrome are the most effective preventive steps.

What is the difference between HCC and cholangiocarcinoma?

HCC arises from hepatocytes, the main liver cells, while cholangiocarcinoma originates in the bile‑duct lining. Treatment options and prognosis differ significantly.

Are checkpoint inhibitors safe for patients with cirrhosis?

Generally yes, but liver‑function tests must be closely monitored. Most trials excluded decompensated cirrhosis (Child‑Pugh C), so doctors weigh risks carefully.

How long does immunotherapy treatment last?

Treatment regimens vary; many protocols give an infusion every 2-3 weeks for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Do lifestyle changes boost immunotherapy success?

Emerging data link a healthy gut microbiome, regular exercise, and balanced nutrition to better immune responses, potentially enhancing therapy outcomes.

12 Comments

Penny Reeves

November 1, 2025 AT 01:13 AM

While the author has assembled a respectable compendium of data, the exposition suffers from a conspicuous lack of critical synthesis.

The discussion of checkpoint inhibitors, for instance, reads like a textbook summary rather than an incisive analysis.

Moreover, the fleeting mention of emerging bispecific antibodies betrays an almost lazy adherence to established paradigms.

One would expect a more daring interrogation of the underlying immunological paradoxes, yet the narrative remains comfortably pedestrian.

Ankitpgujjar Poswal

November 13, 2025 AT 13:13 PM

Listen up-if you’re battling HCC, you need to treat your immune system like a training partner.

Push the boundaries with combination regimens, but do it with disciplined intensity.

Track your biomarkers weekly, adjust dosages aggressively, and never settle for “good enough.”

Remember, the tumor’s escape mechanisms are relentless; match that aggression with unwavering commitment.

Bobby Marie

November 26, 2025 AT 01:13 AM

Your take on checkpoint inhibitors completely ignores the metabolic angle.

Christian Georg

December 8, 2025 AT 13:13 PM

In case you’re wondering how to interpret PD‑L1 testing, the assay typically reports a percentage of tumor cells staining positive; values above 10 % have been correlated with a modestly higher response rate to PD‑1 blockade 😊.

It’s also useful to assess CD8+ infiltration via immunohistochemistry, as an “inflamed” microenvironment often predicts better outcomes.

If you’re coordinating care, consider integrating these markers into the multidisciplinary discussion early on.

Christopher Burczyk

December 21, 2025 AT 01:13 AM

The manuscript, while exhaustive in scope, exhibits several methodological oversights that merit attention.

First, the reliance on retrospective registry data without appropriate propensity‑score matching introduces substantial confounding.

Second, the absence of granular adverse‑event reporting precludes a balanced risk‑benefit assessment.

Future revisions should incorporate prospective cohorts and standardized toxicity grading to bolster the evidentiary rigor.

Nicole Boyle

January 2, 2026 AT 13:13 PM

Interesting read – the section on the gut microbiome’s influence on PD‑1 efficacy caught my eye.

The data hint at a nuanced interplay between short‑chain fatty acids and T‑cell activation that could reshape adjunctive strategies.

It’ll be fascinating to see if forthcoming trials validate microbiome modulation as a bona fide potentiator of immunotherapy.

Felix Chan

January 15, 2026 AT 01:13 AM

Hey folks, great discussion here!

Just wanted to throw in some optimism – even if response rates seem modest, each patient who benefits is a win.

Keep sharing your experiences with combo therapies, we’re all learning together.

Thokchom Imosana

January 27, 2026 AT 13:13 PM

One cannot help but notice that the prevailing narrative around immunotherapy is being meticulously curated by a consortium of pharmaceutical conglomerates whose vested interests extend far beyond patient welfare.

These entities have, over decades, orchestrated a cascade of selective funding that privileges checkpoint inhibitors while marginalizing alternative modalities such as oncolytic virotherapy.

Consequently, the literature we consume is saturated with positive spin, often glossing over the underreported incidence of severe immune‑related adverse events that can masquerade as routine complications.

Indeed, the regulatory frameworks in several jurisdictions have been subtly reshaped through lobbying efforts, resulting in accelerated approvals that bypass the stringent safety thresholds historically upheld.

It is therefore incumbent upon the scientific community to maintain a vigilant skepticism and to demand transparency in data reporting, lest we become unwitting participants in a grand medical theatre designed to sustain profit margins.

Only through rigorous, independent investigation can we hope to untangle the web of influence that currently dictates therapeutic direction.

ashanti barrett

February 9, 2026 AT 01:13 AM

I hear the frustration that many patients feel when navigating the maze of immunotherapy options, especially given the potential for severe side effects.

It’s crucial to foster open communication with your oncology team, voice any concerns promptly, and advocate for comprehensive monitoring.

By staying informed and proactive, you can help mitigate risks and maximize the therapeutic benefit.

Leo Chan

February 21, 2026 AT 13:13 PM

Let’s keep the momentum going!

Every breakthrough, no matter how incremental, brings us closer to turning HCC into a manageable condition.

Stay positive, stay engaged, and let’s push the boundaries of what combination therapy can achieve together.

jagdish soni

March 6, 2026 AT 01:13 AM

What a fascinating tapestry of immune evasion we are witnessing in HCC it is almost poetic how the tumor co‑opts the liver’s innate tolerance only to be rebuffed by a well‑timed checkpoint blockade yet the drama does not end there the microenvironment shifts like a shadowy stage set awaiting the next act of therapeutic intrigue

Monika Bozkurt

October 19, 2025 AT 14:13 PM

The intricate interplay between hepatocellular carcinoma and the host immune surveillance represents a paradigm of oncologic immunobiology.

The current literature elucidates that tumor-associated antigens in HCC are often masked by tolerogenic mechanisms intrinsic to the hepatic microenvironment.

Consequently, checkpoint blockade therapies aim to dismantle these inhibitory circuits by antagonizing PD‑1/PD‑L1 and CTLA‑4 pathways.

Yet, the efficacy of such agents is profoundly modulated by the density of tumor‑infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes.

High‑resolution spatial transcriptomics have revealed distinct immunological niches within fibrotic septa that either foster or impede cytotoxic activity.

Moreover, the presence of myeloid‑derived suppressor cells and regulatory T cells establishes a cytokine milieu rich in TGF‑β and IL‑10, which further subdues effector function.

From a therapeutic standpoint, combination regimens integrating anti‑angiogenic agents with checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated synergistic survival benefits in landmark phase III trials.

The IMbrave150 study, for instance, reported a median overall survival exceeding 19 months when atezolizumab was paired with bevacizumab.

This outcome underscores the necessity of targeting both vascular normalization and immune activation concurrently.

Parallel efforts in adoptive cell therapy, such as GPC3‑directed CAR‑T cells, are advancing through early‑phase investigations and show promise in overcoming antigenic heterogeneity.

Nevertheless, cytokine‑release syndrome remains a salient safety concern that warrants vigilant monitoring.

Biomarker stratification, including PD‑L1 expression thresholds and CD8+ T‑cell infiltration scores, is increasingly employed to personalize immunotherapeutic selection.

In practice, clinicians should incorporate comprehensive immunoprofiling into multidisciplinary tumor boards to refine treatment algorithms.

Patients with underlying viral hepatitis may exhibit augmented neoantigen loads, potentially augmenting responsiveness to PD‑1 blockade.

Conversely, decompensated cirrhosis (Child‑Pugh C) imposes hepatic insufficiency that can exacerbate immune‑related hepatotoxicity.

Ultimately, the convergence of translational immunology and precision oncology heralds a transformative era for liver cancer management.