Key Takeaways

- Rhabdomyosarcoma is a fast‑growing soft‑tissue cancer that mostly affects children.

- The immune system can spot tumor cells, but the cancer often hides or disables those defenses.

- Immunotherapy - from checkpoint blockers to CAR‑T cells - is changing the treatment landscape.

- Clinical trials now test combos that boost T‑cell activity and reduce tumor‑induced suppression.

- Patients and families should ask about immune‑based options early and stay informed on trial eligibility.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a malignant tumor that arises from skeletal muscle progenitors, most often diagnosed in children and adolescents. It accounts for roughly 3‑4% of childhood cancers and can appear in the head, neck, genitourinary tract, or extremities. Because it grows quickly, early detection and multimodal therapy are critical to improve survival.

When you hear the word "immune system," you probably picture white blood cells patrolling your body like tiny security guards. In reality, the system is a complex network of cells, proteins, and signals that constantly scan for anything that looks out of place.

Immune system is a collection of organs, cells (like T cells, B cells, NK cells) and molecules (such as cytokines) that protect the body from infections and abnormal cells.So, why does a tumor like rhabdomyosarcoma often slip past those guards? The answer lies in a tug‑of‑war between the cancer’s tricks and the immune response’s strengths.

How the Body Detects Cancer

When a cell mutates, it may present abnormal proteins on its surface called tumor antigens that alert T cells and natural killer (NK) cells that something is wrong. These antigens are displayed via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, prompting cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to launch an attack.

NK cells add another layer of defense. Unlike T cells, they don’t need a specific antigen match; they sense cells that lack normal “self” signals. When they spot a rhabdomyosarcoma cell with reduced MHC expression, they release perforin and granzymes that can kill the tumor.

Why Rhabdomyosarcoma Evades Immunity

Unfortunately, rhabdomyosarcoma has a few sneaky tricks:

- Low antigen visibility: Some subtypes express very few recognizable antigens, making T‑cell spotting difficult.

- Checkpoint molecule hijacking: Cancer cells often up‑regulate proteins like PD‑L1 that bind to the PD‑1 receptor on T cells, effectively pressing the "pause" button on immune attack.

- Immunosuppressive cytokines: Tumors secrete transforming growth factor‑β (TGF‑β) and interleukin‑10 (IL‑10), which calm down nearby immune cells.

- Regulatory T‑cell (Treg) recruitment: These cells dampen the overall immune response, shielding the tumor.

Think of it as a criminal wearing a disguise, whispering calming music, and bribing the police. The immune system gets confused and often backs off.

Immunotherapy: Turning the Tables

In the last decade, doctors have learned how to pull the "pause" button off T cells and give them new tools to fight. Below is a quick look at the major approaches being tested against rhabdomyosarcoma.

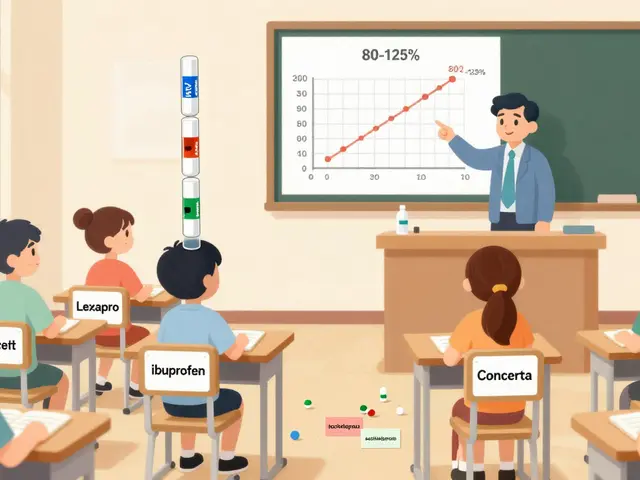

| Modality | Mechanism | Clinical Stage (2025) | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Checkpoint Inhibitors | Block PD‑1/PD‑L1 or CTLA‑4 pathways, re‑activating T cells | Phase I/II trials | Widely available, can combine with chemo | Response rates modest; risk of auto‑immunity |

| CAR‑T Cell Therapy | Engineer patient T cells to target a specific tumor antigen (e.g., GD2) | Phase I trials | Potential for deep, durable responses | Complex manufacturing, cytokine‑release syndrome risk |

| Cancer Vaccines | Introduce tumor‑associated peptides to prime immune memory | Phase I trials | Low toxicity, can be personalized | Often need adjuvants; limited efficacy alone |

| Oncolytic Viruses | Viruses infect tumor cells, causing lysis and immune activation | Early Phase I | Dual action: direct killing + immune boost | Delivery challenges; antiviral immunity may limit repeat dosing |

Each option tackles a different part of the evasion playbook. In practice, many doctors are now testing combos - for example, giving a checkpoint inhibitor alongside a vaccine to "wake up" T cells and then keep them active.

Key Players in the Immune Fight

Understanding the actors helps you ask smarter questions at the clinic.

- Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are the main killers that recognize tumor antigens and destroy cancer cells.

- Natural Killer (NK) cells provide rapid, antigen‑independent killing of stressed or abnormal cells.

- Regulatory T cells (Tregs) act as peacekeepers that can unintentionally protect the tumor by suppressing immune activation.

- PD‑L1 is a protein on tumor cells that binds PD‑1 on T cells to turn off their attack mode.

- CAR‑T cells are patient‑derived T cells engineered to display a synthetic receptor targeting a tumor‑specific antigen such as GD2.

What the Numbers Say

According to the latest pediatric oncology registry (2024), the 5‑year overall survival for localized rhabdomyosarcoma sits around 80%, but drops below 30% for metastatic disease. Early‑phase immunotherapy trials have reported partial responses in 15‑25% of heavily pre‑treated patients, a modest bump that fuels hope for combination strategies.

Practical Steps for Patients & Families

- Ask about immune profiling. Request tests that measure PD‑L1 expression, tumor mutational burden, and infiltrating lymphocytes. These data guide immunotherapy eligibility.

- Explore clinical trials. Websites like ClinicalTrials.gov list studies combining checkpoint blockers with standard chemo for rhabdomyosarcoma. Ask your oncologist whether a trial fits your child’s disease stage.

- Monitor side effects. Immune‑related adverse events can include skin rash, colitis, or thyroid changes. Early reporting lets the care team intervene before problems worsen.

- Stay on top of vaccinations. While receiving immunotherapy, live vaccines (e.g., shingles) are usually avoided, but inactivated vaccines (flu, COVID‑19) are safe and recommended.

- Lean on support networks. Organizations such as the Rhabdomyosarcoma Foundation provide counseling, financial aid, and peer connections.

Looking Ahead

Researchers are now engineering bispecific antibodies that bind both a tumor antigen and a T‑cell receptor, effectively forcing T cells to attack the cancer.

Another hot area is neoantigen vaccines tailored to the unique mutations inside each patient’s tumor, offering a truly personalized immune boost.

These advances suggest that, within the next few years, immunotherapy could move from a niche option to a core pillar of rhabdomyosarcoma treatment, especially for high‑risk or relapsed cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can checkpoint inhibitors cure rhabdomyosarcoma?

At present, checkpoint inhibitors alone rarely achieve cure. They can extend survival and, when paired with chemotherapy or other immune agents, improve response rates. Ongoing trials are testing these combos to see if cure becomes realistic.

Is CAR‑T therapy available for children with rhabdomyosarcoma?

CAR‑T is still in early‑phase trials for this cancer. A few centers offer it under research protocols, usually for patients who have exhausted standard options. Eligibility depends on tumor antigen expression (e.g., GD2).

What side effects should families watch for during immunotherapy?

Common issues include fatigue, skin rash, mild diarrhea, and low blood counts. Rare but serious events are autoimmune attacks on organs like the lung or liver. Prompt reporting to the care team is essential.

Do vaccines interfere with immunotherapy?

Inactivated vaccines are safe and often encouraged to prevent infections that could delay cancer treatment. Live vaccines are generally avoided while the immune system is being modulated.

How can I find a clinical trial for my child?

Start with ClinicalTrials.gov, filter by "rhabdomyosarcoma" and age group. Your pediatric oncologist can also query national cooperative groups like the Children's Oncology Group (COG) for open studies.

12 Comments

michael abrefa busia

October 4, 2025 AT 14:13 PM

Absolutely love the optimism here! 😃💪 Keeping those questions rolling will only make the team pull harder on that pause button. Let’s keep the vibe high and the science rolling! 🚀

Bansari Patel

October 11, 2025 AT 04:33 AM

Rhabdomyosarcoma’s stealth tactics are a stark reminder that cancer evolution can outpace our naive expectations of immune surveillance. When a tumor cloaks itself behind low antigen visibility, it isn’t just hiding – it’s actively rewriting the rules of engagement. The up‑regulation of PD‑L1 is not a passive accident but a calculated hijack of the immune checkpoint circuitry. TGF‑β and IL‑10 secretions act like diplomatic bribes, pacifying the very cells that should roar in defense. Regulatory T‑cells are recruited like corrupt officials, ensuring the jurisdiction stays under the tumor’s control. This layered subterfuge forces us to reconceptualize treatment as a multi‑front battle rather than a single‑arrow strike. Checkpoint inhibitors alone are akin to pulling a single lever on a massive control panel – you’ll get some response, but the system remains largely dormant. CAR‑T cells, while promising, bring their own logistical nightmare, demanding bespoke manufacturing and vigilant monitoring for cytokine storms. Oncolytic viruses, in theory, should be the Trojan horse, yet delivery barriers often leave them stranded at the gates. The emerging bispecific antibodies aim to bridge T‑cell receptors directly to tumor antigens, but their pharmacokinetics still need refinement. Neoantigen vaccines sound like personalized fireworks, but the heterogeneity of rhabdo mutations means each spark may fizzle. Clinical trial data show partial responses in a minority, underscoring the necessity for rational combination strategies. Engaging NK cells alongside T‑cell activation could provide that antigen‑independent punch we desperately need. Moreover, integrating immune profiling into standard work‑ups will empower clinicians to match patients with the right armament. Ultimately, the fight against rhabdomyosarcoma is a chess game where every piece matters, and surrendering to a single tactic is defeat by design.

Rebecca Fuentes

October 17, 2025 AT 18:53 PM

Thank you for the comprehensive analysis. Your delineation of each immunotherapeutic modality provides valuable insight for clinicians navigating treatment options. The emphasis on combinatorial approaches aligns with current research trajectories. I appreciate the scholarly tone and depth presented.

Jacqueline D Greenberg

October 24, 2025 AT 09:13 AM

Totally agree, the blend of therapies feels like the best path forward. It’s reassuring to see such clear guidance, especially for families feeling overwhelmed.

Jim MacMillan

October 30, 2025 AT 22:33 PM

One must acknowledge that the discourse surrounding immunotherapy often suffers from populist oversimplifications. The nuanced interplay of checkpoint pathways, cytokine milieus, and cellular engineering cannot be reduced to headline slogans. As the field matures, discerning scholars will appreciate the stratified evidence hierarchy that underpins these advances. 🤓✨

Dorothy Anne

November 6, 2025 AT 12:53 PM

Spot on! Keeping a balanced view helps us stay grounded while pushing the envelope. Let’s keep championing evidence‑based optimism.

True Bryant

November 13, 2025 AT 03:13 AM

The immuno‑oncologic landscape is riddled with epistemic contingencies that demand a lexicon beyond layman simplifications. When we invoke the term “immune checkpoint blockade,” we invoke a cascade of intracellular phosphorylation events, SHP‑2 recruitment, and transcriptional reprogramming. Failure to appreciate the mechanistic substrates renders therapeutic optimism naïve at best. Moreover, the tumor microenvironment’s hypoxic niche orchestrates a metabolic rewiring that subverts effector T‑cell glycolysis, throttling their cytotoxic potential. Bispecific T‑cell engagers (BiTEs) emerge as a synthetically engineered conduit, yet their pharmacodynamics are constrained by avidity thresholds. The cytokine storm phenomenon, while pathognomonic of CAR‑T activation, reflects a systemic cytokine release syndrome (CRS) that necessitates IL‑6 blockade deliberations. In the context of rhabdomyosarcoma, antigenic heterogeneity compounds the challenge of target selection, demanding multiplexed strategies. Concurrently, the paucity of neoantigen burden in pediatric cohorts attenuates the immunogenicity ceiling. Therefore, a convergent paradigm integrating epigenetic modulators, oncolytic virotherapy, and adaptive cellular platforms may constitute the next frontier. Nonetheless, rigorous biomarker stratification remains the linchpin to translate these theoretical constructs into clinical reality.

Danielle Greco

November 19, 2025 AT 17:33 PM

Great summary!

Linda van der Weide

November 26, 2025 AT 07:53 AM

Thanks! Glad you found it helpful.

Philippa Berry Smith

December 2, 2025 AT 22:13 PM

It’s almost suspicious how quickly these “breakthroughs” appear, as if a shadowy consortium is pushing expensive therapies without solid data. One can’t help but wonder if pharmaceutical interests are steering trial designs to maximize profit rather than patient benefit. The hype around CAR‑T often glosses over the hidden costs and long‑term toxicities that are conveniently omitted from press releases. I remain skeptical until transparent, independent studies prove real, durable outcomes for children.

Joel Ouedraogo

December 9, 2025 AT 12:33 PM

While skepticism is warranted, dismissing emerging modalities outright ignores the empirical evidence accumulating from rigorously conducted trials. The ethical imperative is to balance caution with the potential for life‑saving breakthroughs, especially in refractory pediatric cancers. Constructive discourse, not conspiratorial dismissal, will propel the field forward. Let’s focus on data transparency and patient‑centered outcomes.

Matthew Balbuena

September 28, 2025 AT 00:01 AM

Hey fam, just wanted to say that the way the immune system can actually hunt down rhabdo cells is truly mind‑blowing, even if the tumor tries to pull a fast one. The checkpoint stuff is like hitting the snooze button on a fire alarm – you gotta yank it out fast. If you’re thinkin about trials, definitely bring up PD‑L1 testing at the next visit – it could open doors. Remember, therapy combos are kinda like a band; each instrument matters, so stay curious and keep askin questions.