Key Takeaways

- UTIs can set off immune pathways that linger long after the infection clears.

- Post‑infectious fatigue is a recognised trigger for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS).

- Inflammation, dysbiosis, and mast‑cell activation link bladder infections to systemic tiredness.

- Early diagnosis, targeted antibiotics, and microbiome support can reduce the risk of chronic fatigue.

- Watch for red‑flag symptoms-persistent brain fog, unrefreshing sleep, and pain-that suggest CFS after a UTI.

Understanding Urinary Tract Infections

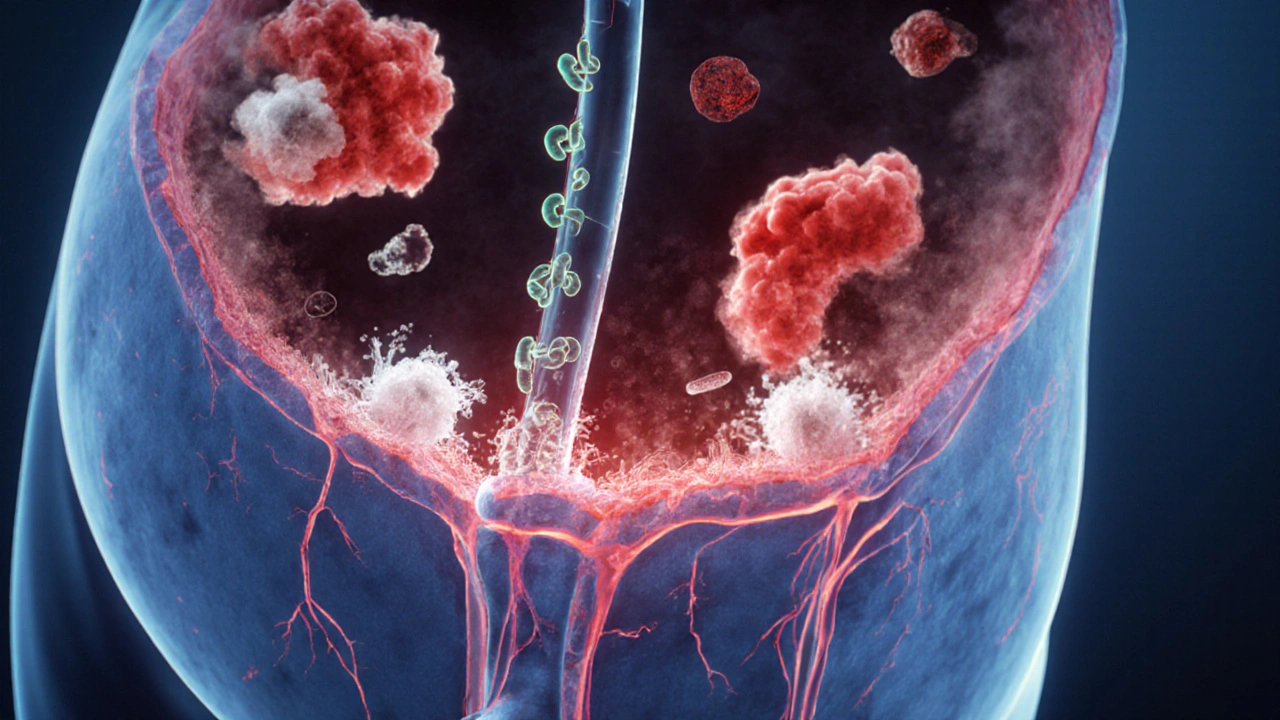

When doctors refer to a Urinary Tract Infection is a bacterial invasion of any part of the urinary system, most often the bladder (cystitis), they’re describing a condition that touches roughly 150million people worldwide each year. The most common culprit is Escherichia coli (E. coli), a gut bacterium that can travel up the urethra and multiply in urine.

Typical symptoms-burning during urination, frequent urges, and cloudy urine-last from a few days to a couple of weeks. Most cases clear with a short course of Antibiotics (drugs that kill or inhibit bacterial growth), but a subset of patients experience lingering inflammation.

What Is Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) is a complex, disabling disorder marked by profound, unexplained fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest. Diagnosis hinges on the 2021 Institute of Medicine criteria: persistent fatigue≥6months, post‑exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and either cognitive impairment or orthostatic intolerance.

Patients often report a “flu‑like” onset, sometimes after a viral infection, but bacterial triggers-like UTIs-are increasingly recognized in the medical literature.

How Infections Can Spark Chronic Fatigue

Post‑infectious fatigue is not just a feeling of being tired after being sick; it’s a measurable shift in the Immune System (the network of cells and molecules that defend the body). When a pathogen breaches a barrier, the body releases cytokines (e.g., IL‑6, TNF‑α) to fight it. In some people, this response overshoots, leaving a “cytokine haze” that can last weeks or months.

Researchers have identified three recurring pathways that turn an acute infection into chronic fatigue:

- Sustained inflammation that interferes with mitochondrial energy production.

- Altered gut‑bladder axis leading to Dysbiosis (an imbalance of microbial communities) and leaky gut.

- Activation of Mast Cells (immune cells that release histamine and other mediators), which can cause systemic pain and brain fog.

Overlapping Biological Pathways Between UTIs and CFS

While a bladder infection feels local, the body doesn’t keep it compartmentalized. Here’s how a UTI can nudge the system toward chronic fatigue:

- Inflammatory spill‑over: Even a short‑lived cystitis spikes IL‑1β and CRP, markers that travel through the bloodstream and reach the brain.

- Microbial translocation: E. coli can form biofilms on the urothelium, making it harder for antibiotics to eradicate the bacteria completely.

- Dysbiosis cascade: Antibiotic treatment, while necessary, can wipe out beneficial gut flora, allowing opportunistic species to flourish and produce neuro‑active metabolites.

- Mast‑cell sensitization: The bladder wall houses abundant mast cells. Repeated irritation may prime these cells, leading to systemic release of histamine that aggravates fatigue and cognitive fog.

These mechanisms dovetail with the core features of CFS, explaining why some patients report a “U‑shaped” health curve-feeling fine, then a UTI, then a gradual decline into chronic exhaustion.

Scientific Evidence Linking UTIs to Chronic Fatigue

A 2022 prospective cohort study of 2,300 women tracked fatigue scores for six months after a documented UTI. Those whose infection required more than one antibiotic course had a 2.4‑fold higher risk of meeting CFS criteria versus women whose infection resolved after a single dose.

Another small‑scale trial from 2023 examined cytokine profiles in 48 patients post‑UTI. Participants who developed persistent fatigue showed elevated IL‑6 and reduced mitochondrial ATP production, patterns identical to classic CFS cohorts.

Case reports from rheumatology clinics also note that patients with recurrent cystitis often present with “post‑infectious” CFS, responding partially to mast‑cell stabilizers like cromolyn.

Practical Steps for Patients and Clinicians

Early recognition is key. If a patient reports a UTI followed by lingering brain fog, unrefreshing sleep, or exercise intolerance, consider the following workflow:

- Confirm the infection: Urine culture, sensitivity panel, and possibly a PCR test for atypical bacteria (e.g., Mycoplasma genitalium).

- Choose targeted antibiotics: Base therapy on culture results; avoid broad‑spectrum agents when a narrow‑spectrum drug will suffice.

- Monitor inflammation: Serial CRP and cytokine panels can flag ongoing immune activation.

- Support the microbiome: Introduce Probiotics (live beneficial microorganisms) such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG during and after antibiotic therapy.

- Address mast‑cell activation: If symptoms include flushing, itching, or hives, a low‑dose antihistamine or mast‑cell stabilizer may be warranted.

- Energy‑management plan: Pacing, graded exercise therapy (only under professional guidance), and sleep hygiene reduce the risk of transitioning to full‑blown CFS.

Patients who follow this structured approach often report a quicker return to baseline energy levels and a lower chance of chronic fatigue.

Prevention Tips to Keep Your Bladder-and Energy-Healthy

- Drink at least 2liters of water daily; urine dilution reduces bacterial adhesion.

- Urinate soon after sexual activity to flush potential pathogens.

- Avoid irritants such as harsh soaps, douches, and prolonged tight clothing.

- Consider cranberry extract or D‑mannose supplements, which can inhibit bacterial binding to the urothelium.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in fiber to support gut‑microbial diversity, indirectly protecting the bladder.

When to Seek Specialist Care

If fatigue persists beyond four weeks after completing antibiotics, or if you experience any of the following, book an appointment with a specialist (urologist, immunologist, or a CFS clinic):

- Continuous low‑grade fever or night sweats.

- Worsening brain fog that interferes with work or study.

- Orthostatic intolerance-feeling dizzy or light‑headed when standing.

- Joint or muscle pain that isn’t relieved by over‑the‑counter analgesics.

Early referral can fast‑track additional testing, such as autonomic function labs or advanced imaging, that may uncover hidden contributors.

Symptom Overlap: UTI vs. CFS

| Symptom | Typical in UTI | Typical in CFS |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | Occasional, improves with rest | Persistent, unrelieved by sleep |

| Brain fog | Rare | Common, affects concentration |

| Urinary urgency | Frequent, painful | May appear secondary to bladder irritation |

| Night sweats | Occasional | Frequent, disrupts sleep |

| Muscle aches | Localized pelvic area | Widespread, often severe |

Quick Checklist for Post‑UTI Fatigue

- Did fatigue last more than 4weeks after antibiotics?

- Are you experiencing unrefreshing sleep or post‑exertional malaise?

- Is there any lingering urinary discomfort?

- Have inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR) normalized?

- Are you taking probiotic support to restore gut flora?

If you answer “yes” to two or more items, schedule a follow‑up with a healthcare professional.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a single UTI cause chronic fatigue?

Yes, in some people a one‑off infection can trigger a prolonged immune response that leads to post‑infectious fatigue. The risk rises if the infection is severe, recurrent, or treated with broad‑spectrum antibiotics that disturb the gut microbiome.

Should I take antibiotics for every UTI if I’m worried about fatigue?

Antibiotics are essential when a bacterial infection is confirmed. However, a targeted, short‑course regimen based on culture results reduces unnecessary exposure and helps preserve the gut flora, which can lessen the chance of lingering fatigue.

Are probiotics proven to prevent post‑UTI fatigue?

Research shows probiotics can shorten the recovery of gut diversity after antibiotics and may blunt the inflammatory cascade. While not a guaranteed shield, they are a low‑risk adjunct that many clinicians recommend.

What red‑flag symptoms mean I should see a specialist?

Persistent high‑grade fever, worsening brain fog, orthostatic intolerance, severe joint pain, or fatigue that immobilizes daily tasks all warrant referral to a urologist, immunologist, or a dedicated CFS clinic.

Is there a diet that helps after a UTI?

A high‑fiber, low‑sugar diet supports beneficial gut bacteria. Including foods rich in vitaminC, D‑mannose, and anti‑inflammatory omega‑3 fats can aid bladder healing and reduce systemic inflammation.

10 Comments

Maggie Hewitt

October 24, 2025 AT 04:55 AM

Yeah, because taking a probiotic after a UTI is obviously the secret to eternal energy.

Mike Brindisi

November 2, 2025 AT 15:55 PM

UTIs trigger immune pathways that don’t just stay in the bladder they spill over into the bloodstream causing systemic inflammation that can affect mitochondria leading to reduced ATP production this cascade is well documented in the literature and it shows why some patients flag chronic fatigue after an infection the gut‑bladder axis gets disrupted the microbiome suffers from antibiotic exposure and that imbalance can produce neuroactive metabolites which then influence brain function so the connection is not just theoretical it’s a real physiological chain reaction that clinicians should watch for.

Steven Waller

November 12, 2025 AT 03:55 AM

Considering the interplay between local infection and systemic energy systems, it becomes clear that the body operates as an integrated whole rather than a collection of isolated parts. The inflammatory spill‑over you mention is not merely a biochemical footnote; it reshapes neural signaling pathways that govern perception of fatigue. From a philosophical standpoint, this challenges the Cartesian split between mind and body that modern medicine often reproduces. By acknowledging that a bladder irritation can echo in cognitive fog, we honor the embodied nature of health. In practice, this suggests clinicians should adopt a more holistic monitoring regime post‑UTI, not just a repeat urine culture.

Puspendra Dubey

November 21, 2025 AT 15:55 PM

Ah, the drama of the humble UTI evolving into a full‑blown saga of chronic exhaustion! Who would have thought that a pesky bug in the bladder could unleash such a tempest of cytokines, mast cells, and existential dread? 😱 My gut tells me the microbiome is like a fickle orchestra-once antibiotics take the lead, chaos reigns until the right probiotics step back onto the stage. And don't even get me started on the "U‑shaped" health curve – it's practically the plot twist of a medical thriller! 🌟 But seriously, folks, keep an eye on those lingering brain‑fog symptoms; the body loves to whisper before it shouts. 🙃

Shaquel Jackson

December 1, 2025 AT 03:55 AM

Well, that's an interesting take… maybe we should all start fearing our own bladders now? 😅

Tom Bon

December 10, 2025 AT 15:55 PM

While the data presented is compelling, it is advisable for clinicians to incorporate routine inflammatory marker assessments following antibiotic therapy. Such an approach aligns with evidence‑based practice and may mitigate progression to chronic fatigue. Moreover, patient education regarding hydration and probiotic supplementation should be delivered in a clear, courteous manner.

Clara Walker

December 20, 2025 AT 03:55 AM

Don't be fooled by the "evidence‑based" rhetoric – this is just another way for the pharmaceutical lobby to push unnecessary antibiotics and keep us dependent. The real culprits are hidden governmental programs manipulating our microbiomes for control. Wake up, people!

Jana Winter

December 29, 2025 AT 15:55 PM

While I respect the passion behind your message, there are several factual inaccuracies. First, the term "pharmaceutical lobby" is overgeneralized and not supported by peer‑reviewed studies cited here. Second, claims of "governmental programs" lack credible evidence. Please ensure future statements are grounded in verifiable data.

Linda Lavender

January 8, 2026 AT 03:55 AM

In the grand tapestry of medical literature, the interrelationship between urinary tract infections and chronic fatigue syndrome emerges as a motif worthy of deep contemplation. The pathophysiological narrative begins with a seemingly innocuous incursion of Escherichia coli into the urothelial sanctum, a microbe whose virulence is amplified by the formation of resilient biofilms. These structures serve not only as a protective enclave for the pathogen but also as a catalyst for sustained inflammatory cascades, releasing interleukins such as IL‑1β and tumor necrosis factor‑α into the systemic circulation. This cytokine surge, in turn, traverses the blood‑brain barrier, engendering a milieu of neuroinflammation that manifests as the hallmark "brain fog" observed in many post‑infectious fatigue cases.

Simultaneously, the obligatory therapeutic intervention-antibiotic administration-exerts collateral damage upon the commensal gut microbiota. The resultant dysbiosis disrupts the gut‑bladder axis, fostering an overgrowth of opportunistic species capable of producing neuroactive metabolites, including short‑chain fatty acids and tryptophan derivatives. These metabolites, once liberated into the portal circulation, exert profound effects on mitochondrial function, attenuating ATP synthesis and precipitating the profound energy deficits characteristic of chronic fatigue syndrome.

Moreover, the bladder's native mast cells, when repeatedly provoked, become hyperresponsive. Their degranulation disseminates histamine and other vasoactive substances throughout the body, amplifying peripheral pain sensations and perpetuating the cycle of fatigue. This phenomenon aligns with emerging data on mast‑cell activation syndrome (MCAS) as a comorbid condition in a subset of CFS patients, further complicating the clinical picture.

Clinical implications are manifold. Early identification of post‑UTI fatigue requires vigilance for red‑flag symptoms persisting beyond the typical convalescent window of four weeks. Serial measurement of inflammatory biomarkers-C‑reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and cytokine panels-can provide objective corroboration of ongoing immune activation. Tailored antimicrobial stewardship, guided by urine culture sensitivities, minimizes unnecessary broad‑spectrum exposure, thereby preserving microbial diversity.

Adjunctive strategies, such as targeted probiotic regimens (e.g., Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) and mast‑cell stabilizers like cromolyn sodium, have demonstrated modest efficacy in attenuating symptom severity. Nutritional optimization, emphasizing high‑fiber, low‑sugar diets rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, further supports gut integrity and attenuates systemic inflammation.

In sum, the convergence of immunological, microbial, and neurochemical pathways elucidates how a localized urinary infection can precipitate a systemic state of chronic fatigue. Recognizing this intricate interplay empowers clinicians to intervene preemptively, potentially averting the transition from an acute infection to a debilitating, lifelong syndrome.

Matt Cress

October 14, 2025 AT 16:55 PM

Oh great, another article telling us that a simple bladder bug can turn you into a human batterry-because who doesn't love a dose of extra fatigue with their morning coffee?