DRESS Syndrome Risk Calculator

RegiSCAR Criteria Assessment

DRESS syndrome requires careful diagnosis using the RegiSCAR scoring system. This tool helps assess the likelihood of DRESS based on key clinical criteria. Remember: This is not a diagnostic tool. If symptoms are present, seek immediate medical attention.

Enter criteria and click "Calculate Score" to assess potential DRESS risk.

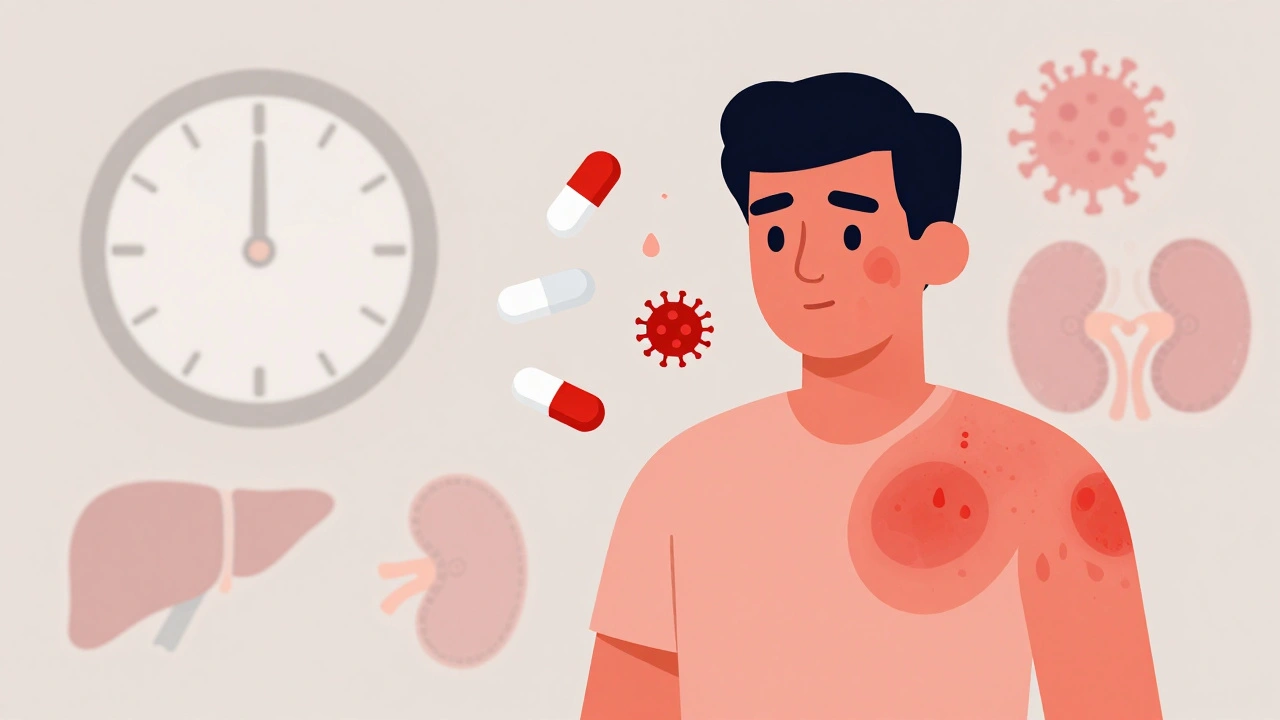

DRESS syndrome isn’t just a rash. It’s a full-body alarm system triggered by a medication you likely thought was harmless. Imagine taking a pill for gout, epilepsy, or an infection, and weeks later, your body turns against you-fever spikes, your skin breaks out in angry red patches, your liver swells, and your blood fills with abnormal white cells. This isn’t an allergy you can treat with antihistamines. This is Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms, or DRESS, and it kills about 1 in 10 people who get it if not caught fast.

How DRESS Starts-And Why It’s So Hard to Spot

DRESS doesn’t show up the day after you take a new drug. It waits. Usually between 2 and 8 weeks. That’s the first trap. Most doctors think of rashes as immediate reactions-something that happens right after a penicillin shot or a new antibiotic. But DRESS hides. It sneaks in slowly, mimicking a bad virus: fatigue, low-grade fever, swollen glands. By the time the rash appears, it’s often already too late.

The rash? It’s not pretty. Starts on the face and chest as flat, red spots that spread like wildfire, covering up to 90% of your skin. Swelling around the eyes and lips is common. You might feel like you’ve got the flu-but without the cough or runny nose. And here’s what makes it dangerous: your internal organs start failing. The liver is hit hardest-78% of cases show ALT levels above 300 IU/L, sometimes over 1,000. Your kidneys, lungs, heart, even your pancreas can get dragged into the chaos.

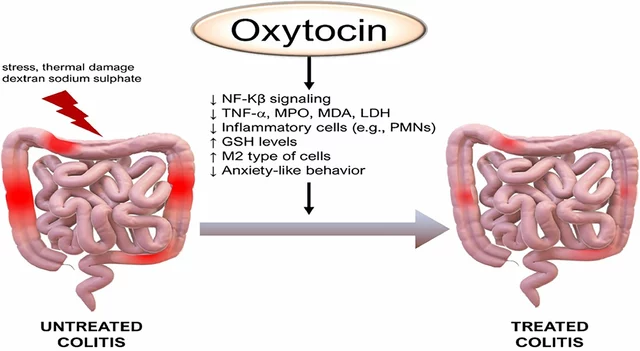

And then there’s the blood. Eosinophils-white blood cells that usually fight parasites-spike to over 1,500 per microliter. In some cases, they hit 5,000. That’s not normal. That’s your immune system in full meltdown mode. And in 60-80% of cases, a dormant virus-usually HHV-6-gets reactivated, adding fuel to the fire. This isn’t just a drug reaction. It’s a perfect storm of drug, gene, and virus.

Who’s at Risk? The Real Culprits Behind DRESS

Not every drug causes DRESS. But some are notorious. Allopurinol, used for gout, is the biggest offender-responsible for nearly 30% of cases. If you’re Asian and carry the HLA-B*58:01 gene, your risk skyrockets. In Taiwan, doctors test for this gene before prescribing allopurinol. Since 2012, DRESS cases from this drug have dropped by 80%.

Anticonvulsants like carbamazepine and phenytoin come next. If you have HLA-A*31:01, you’re at higher risk. That’s why in Japan and South Korea, these drugs come with mandatory genetic screening warnings. In the U.S.? No such rule. You could be prescribed carbamazepine for migraines or nerve pain-and never know you’re playing Russian roulette with your life.

Antibiotics like vancomycin, minocycline, and sulfonamides are also common triggers. Even some NSAIDs and antiretrovirals have been linked. The common thread? These drugs are metabolized slowly, linger in your system, and can trigger immune chaos in genetically vulnerable people.

And here’s the kicker: your doctor probably doesn’t know this. A 2021 study found only 38% of primary care doctors could correctly identify DRESS. Most patients visit the ER two to five times before someone finally connects the dots. One Reddit user wrote: ‘Went to the ER three times. First told it was a virus. Then allergies. At week seven, liver enzymes hit 1,200-that’s when they said DRESS.’

The Gold Standard: How DRESS Is Diagnosed

There’s no single test for DRESS. Diagnosis relies on a scoring system called RegiSCAR, developed in 2007 and still the gold standard today. It looks at six key criteria: fever, rash, enlarged lymph nodes, blood abnormalities (eosinophils, atypical lymphocytes), organ involvement, and timing after drug exposure. A score of 5 or higher means probable DRESS. 6 or higher? Definite.

But here’s what doctors must do beyond the score:

- Stop the suspected drug-immediately. No waiting. No ‘let’s see if it gets better.’

- Run a full blood count with differential-eosinophils are the red flag.

- Check liver enzymes (ALT, AST), kidney function (creatinine), and viral serologies (HHV-6, EBV, CMV, hepatitis).

- Rule out infections like mononucleosis or hepatitis that mimic DRESS.

- Look for HLA genes if the drug is allopurinol or carbamazepine.

And yes-this is a medical emergency. If your ALT is above 1,000 or your creatinine is over 2.0, you need ICU-level monitoring. Delayed treatment raises death risk by 40%.

What Happens After Diagnosis? Treatment and Recovery

There’s no cure. But there’s control. The first step is always stopping the drug. Then comes steroids. Prednisone is the go-to. It’s not perfect-there are no big randomized trials proving it works-but every expert agrees: start it within 72 hours, and your odds of survival jump dramatically. Studies show 60-70% of patients respond well if treated early.

But steroids aren’t a quick fix. You’re looking at 3 to 6 months of tapering. Drop too fast, and the inflammation comes roaring back. One patient, Sarah Johnson, took 6 months to come off prednisone after vancomycin-induced DRESS. She returned to work as a nurse-but she had to relearn how to breathe without coughing.

For those who don’t respond to steroids? Options are limited. IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) and mycophenolate are being tested in trials. A new phase 2 trial at Vanderbilt, started in March 2023, is testing IVIG plus mycophenolate to reduce steroid dependence. Early results are promising.

Recovery isn’t guaranteed. About 1 in 5 patients develop long-term problems: chronic liver damage, autoimmune thyroid disease, kidney scarring. One 2022 case report described a 42-year-old man who developed permanent kidney failure after 22 days of missed diagnosis. He never recovered.

Why DRESS Is Getting Worse-And What’s Changing

DRESS is rising. Why? More people are on long-term medications. More people are being tested for HLA genes. And more people are surviving-because we’re getting better at recognizing it.

But disparities are huge. In Taiwan, universal HLA screening for allopurinol is standard. In the U.S.? Not even close. The average hospital stay for DRESS costs $28,500. Yet most community hospitals don’t have protocols. Academic centers? They do. That means your survival depends on where you live-and who you see.

Change is coming. In March 2023, the FDA approved the first point-of-care test for HLA-B*58:01. It gives results in under an hour. That means, soon, before you even get your first allopurinol pill, your doctor could run a quick cheek swab and know if it’s safe.

And there’s a global DRESS registry now-launched in September 2023-with 47 sites across 18 countries. It’s collecting data on triggers, outcomes, and long-term effects. This isn’t just science. It’s saving lives.

What You Should Do Now

If you’re on allopurinol, carbamazepine, phenytoin, or any antibiotic and develop a rash after 2+ weeks-don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s ‘just an allergy.’ Go to the ER. Demand a complete blood count with differential and liver enzymes. Ask: ‘Could this be DRESS?’

If you’re a patient with a history of severe skin reactions, ask your doctor about HLA testing before starting new drugs. If you’re a doctor-learn the RegiSCAR criteria. Use the mobile app. Don’t wait for a textbook case. DRESS doesn’t wait.

The truth? DRESS is rare. But it’s not rare enough. And every day without awareness, someone slips through the cracks. You don’t need to be a specialist to save a life. You just need to know when to ask the right question.

13 Comments

Shannon Gabrielle

December 3, 2025 AT 12:38 PM

So let me get this straight-we’ve got a deadly drug reaction that’s 80% preventable with a genetic test, but we’d rather wait until someone’s liver is fried and their skin is peeling off like a bad sunburn?

Classic America. We’ll spend $20K on a ventilator but won’t spend $5 on a DNA swab. Next they’ll charge us extra to not die from common sense.

Also-HHV-6 reactivation? Yeah, that’s the real villain. Not the drug. Not the gene. The virus that’s been chilling in your spine since you were 8. Thanks, childhood.

Also also-why is no one talking about how the pharmaceutical industry lobbies against mandatory screening? Just saying.

Also also also-my cousin got DRESS from carbamazepine. He’s now on dialysis. And the doctor who prescribed it? Still practicing. Still prescribing.

Good job, healthcare.

👏

Nnaemeka Kingsley

December 3, 2025 AT 22:06 PM

Man this is real. I had a friend back home in Nigeria take allopurinol for gout, got rash after 3 weeks, went to clinic 4 times, they said ‘heat rash.’ Then he collapsed. Liver all messed up. Took 2 weeks before someone said ‘maybe DRESS.’ He survived but lost 30 pounds. No one here even knows this thing exists. We need education, not just tests.

Doctors here think if you’re not in USA or Europe, you don’t get these fancy diseases. But we get them too. Just slower. And with less help.

Pls share this. Someone’s life depends on it.

Kshitij Shah

December 4, 2025 AT 05:56 AM

Y’all in the US act like DRESS is some newfangled Western disease. Bro, we’ve been seeing this in India since the 90s with sulfonamides and phenytoin. Only difference? We didn’t have the fancy RegiSCAR score-we had grandmas yelling ‘Stop that medicine, his skin is burning!’

And now you’re acting like the FDA’s new cheek swab test is some miracle? We’ve had HLA testing in Mumbai for 15 years. You just didn’t care until it hit your rich white cousin.

Global health isn’t about who tests first. It’s about who gets saved first.

Also-why is no one mentioning how steroids are basically a gamble? I’ve seen people get DRESS, get steroids, then develop diabetes and osteoporosis. So now you’re alive… but broken.

Real talk: medicine is a lottery. And we’re all just holding tickets.

Tommy Walton

December 5, 2025 AT 14:29 PM

Existential question: if a drug kills you slowly while mimicking a virus… does it even count as a ‘side effect’? Or is it just the universe whispering, ‘You shouldn’t have taken that pill’? 🤔

Also-HLA-B*58:01? That’s not a gene. That’s a death sentence with a prescription label. And we’re still handing out allopurinol like it’s candy? Bro. We’re not saving lives. We’re running a genetic roulette wheel.

Also also-DRESS isn’t rare. It’s just underreported. Like grief. Like loneliness. Like truth in American medicine. 🧠🩺

James Steele

December 7, 2025 AT 06:57 AM

The RegiSCAR criteria are elegant in their clinical rigor, yet tragically underutilized in community practice-a microcosm of the broader epistemic fragmentation plaguing contemporary medical education. The disconnect between academic knowledge and frontline execution is not merely logistical; it is ontological.

Moreover, the pharmacogenomic disparity between high-income and low-resource settings isn’t an oversight-it’s a structural violence masquerading as healthcare equity. The fact that HHV-6 reactivation is now recognized as a key immunological amplifier underscores the necessity of a systems biology approach to iatrogenic pathology.

And yet-we still treat DRESS as a diagnostic afterthought rather than a paradigm-shifting model for precision medicine. The irony is… poetic.

Also, prednisone? A blunt instrument in a scalpel’s world. We need targeted immunomodulators. Not steroids. Not IVIG. Not hope. Science.

Louise Girvan

December 8, 2025 AT 08:37 AM

Wait-so the FDA approved a cheek swab test… but didn’t force hospitals to use it? 🤨

And you think this isn’t connected to Big Pharma? They profit from ER visits. From ICU stays. From lifelong dialysis. From patients who never know why they got sick.

And now you’re telling me we’re supposed to trust doctors who didn’t even know what DRESS was in 2021? 😭

They’re not incompetent. They’re complicit.

And the ‘global registry’? Cute. 47 sites? That’s less than 1% of hospitals worldwide. It’s a PR stunt. A distraction. A Band-Aid on a severed artery.

Someone’s making money off this. And it’s not you.

Wake up.

…I’m watching you, FDA.

soorya Raju

December 9, 2025 AT 22:16 PM

HAHAHAHA DRESS? Nah man. This is all a lie. Allopurinol is fine. The real cause? 5G. Or maybe the vaccines. Or the water. Or the moon. I read on a forum that DRESS is just a cover-up for people who got too much glyphosate. Also, the HLA test? That’s how they track you. They’re putting microchips in your DNA.

My cousin’s dog got a rash after eating kibble. Same thing. They just renamed it DRESS to sell more steroids.

Also-why is no one talking about the fact that HHV-6 is just a government bioweapon? They put it in the vaccines to test immune collapse. It’s all connected.

Ask yourself: who benefits? Not you. Not me. But the people who own the labs.

Free your mind.

…and your liver.

Dennis Jesuyon Balogun

December 11, 2025 AT 14:01 PM

This is the kind of post that makes me believe medicine can still be human-if we choose to be. DRESS isn’t just a syndrome. It’s a mirror. It shows us where we’ve stopped listening. Where we treat symptoms instead of stories.

That patient who went to the ER five times? She wasn’t just sick. She was ignored. Rejected. Dismissed. And that’s the real virus.

Genes matter. Viruses matter. Drugs matter.

But so does the person holding the chart.

Let’s not wait for a test to tell us to care. Let’s start caring before the rash appears.

And to the doctors reading this: you don’t need a scorecard to see pain. You just need to look.

We’re not here to diagnose. We’re here to hold space.

And sometimes-that’s the only cure left.

Grant Hurley

December 12, 2025 AT 10:34 AM

Bro this is wild. I had no idea. I take allopurinol for gout. I just thought the rash I got last month was from my new detergent. 😅

Just went and looked up my HLA status-turns out I’m HLA-B*58:01 positive. Holy crap. I’m gonna call my doctor tomorrow and ask for a different med.

Thanks for posting this. You just saved me from a nightmare. Seriously. I’m telling everyone I know.

Also-why isn’t this on every pharmacy label? Like, at least a tiny warning? ‘This might kill you if you’re Asian.’ Just a heads up, guys.

Peace out. Stay safe.

Lucinda Bresnehan

December 14, 2025 AT 04:36 AM

I’m a nurse who worked in ICU for 12 years. Saw three DRESS cases. One died. Two survived-but one now has autoimmune thyroid disease and needs lifelong meds. The other? Still gets flare-ups when she’s stressed.

Here’s what no one tells you: DRESS doesn’t end when the rash fades. The body remembers. Your immune system gets rewired. You’re never the same.

And yes-doctors miss it. All the time. Not because they’re dumb. Because they’re tired. Overworked. Undertrained.

But here’s the good news: if you know the signs, you can save someone. Just ask for a CBC with diff. Just ask. One question. One moment. That’s all it takes.

Don’t wait for a textbook. Don’t wait for a specialist. Be the person who says, ‘What if it’s DRESS?’

You don’t need to be a doctor. Just be brave.

Sean McCarthy

December 15, 2025 AT 00:13 AM

Allopurinol is dangerous. Carbamazepine is dangerous. Steroids are dangerous. IVIG is dangerous. HLA testing is expensive. Hospitals are understaffed. Patients are ignored. Doctors are burned out. The system is broken. We are all just waiting for the next person to die. And when they do, we’ll all be shocked. Again.

Nothing changes. Nothing ever changes.

Just keep taking your pills.

Linda Migdal

December 16, 2025 AT 21:56 PM

Grant, your comment is exactly why we’re losing this battle. You’re grateful you caught it in time-but what about the 10 people who didn’t? You didn’t just save yourself. You exposed the system’s failure.

And now you’re gonna go back to your life like nothing happened?

That’s the real tragedy.

Write to your state rep. Demand HLA screening mandates. Share this post with your doctor. Make noise.

Survival isn’t luck. It’s activism.

Don’t stop at ‘I’m safe.’ Make sure no one else has to suffer like you almost did.

Linda Migdal

December 2, 2025 AT 07:07 AM

DRESS is a nightmare because American medicine is still stuck in the 1990s. We test for everything except the things that actually kill people. In Taiwan, they screen for HLA-B*58:01 before giving allopurinol. Here? You get a prescription, go home, and hope your liver doesn’t turn to mush. This isn’t negligence-it’s systemic laziness wrapped in a white coat.

And don’t get me started on the FDA. They approved a point-of-care HLA test in March 2023 but haven’t mandated its use. That’s not innovation-that’s corporate cowardice. We’re paying $28,500 per hospitalization because we refuse to spend $5 on a cheek swab.

Stop calling it ‘rare.’ It’s rare because we don’t look for it. Change the system or keep burying people under misdiagnosed rashes.