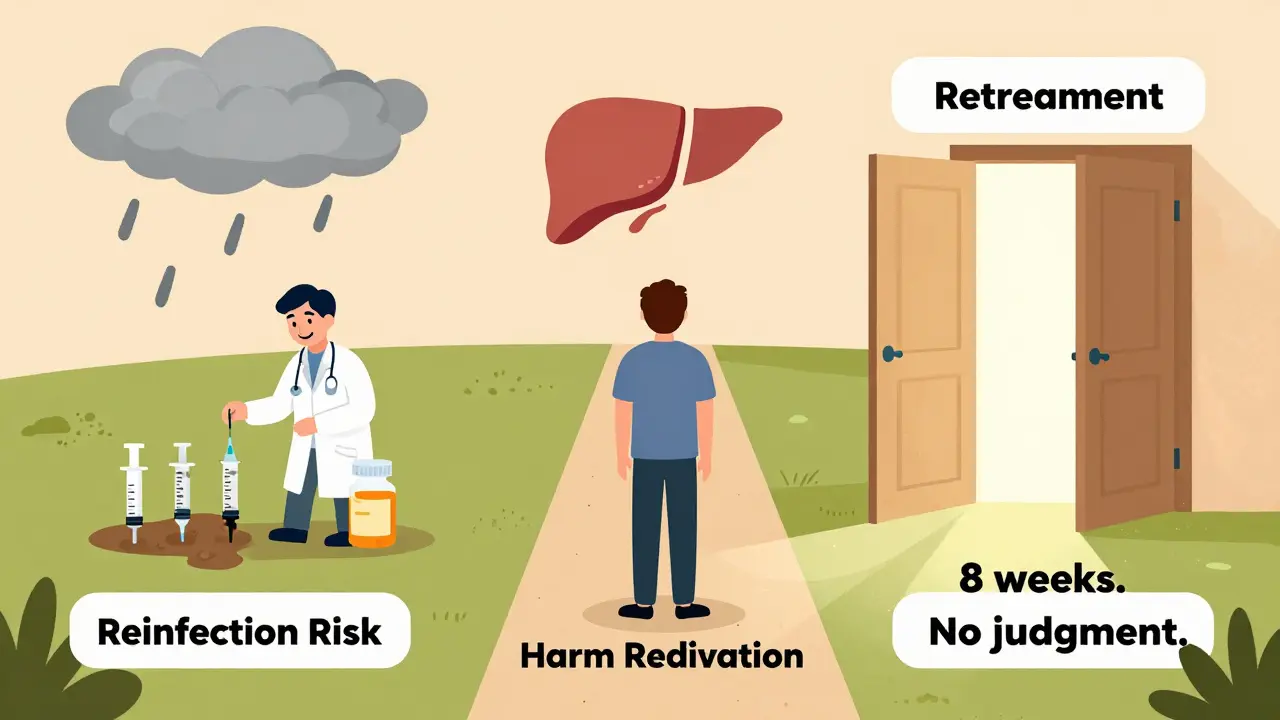

After beating hepatitis C with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), many people think they’re done. But for some, the virus comes back. Not because the treatment failed, but because they’re still exposed to the same risks that got them infected in the first place. This is HCV reinfection-and it’s not a sign of failure. It’s a signal that we need better support, not judgment.

Reinfection Is Real-And It’s Not Rare

People who inject drugs (PWID) are the most likely to get HCV again after being cured. In fact, studies show that within two years of being cured, up to 1 in 5 PWID with ongoing drug use get reinfected. That’s not because the drugs don’t work. It’s because the virus is still circulating in their environment. Needle sharing, unsterile equipment, and lack of access to clean supplies keep the chain alive. The good news? The same drugs that cured you the first time work just as well the second, third, or even fourth time. A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open confirmed that retreatment success rates match those of first-time treatment: 95% or higher. No one should be denied care because they got infected again. The CDC says clearly: treat as often as needed. No stigma. No waiting.How HCV Treatment Has Changed Since 2014

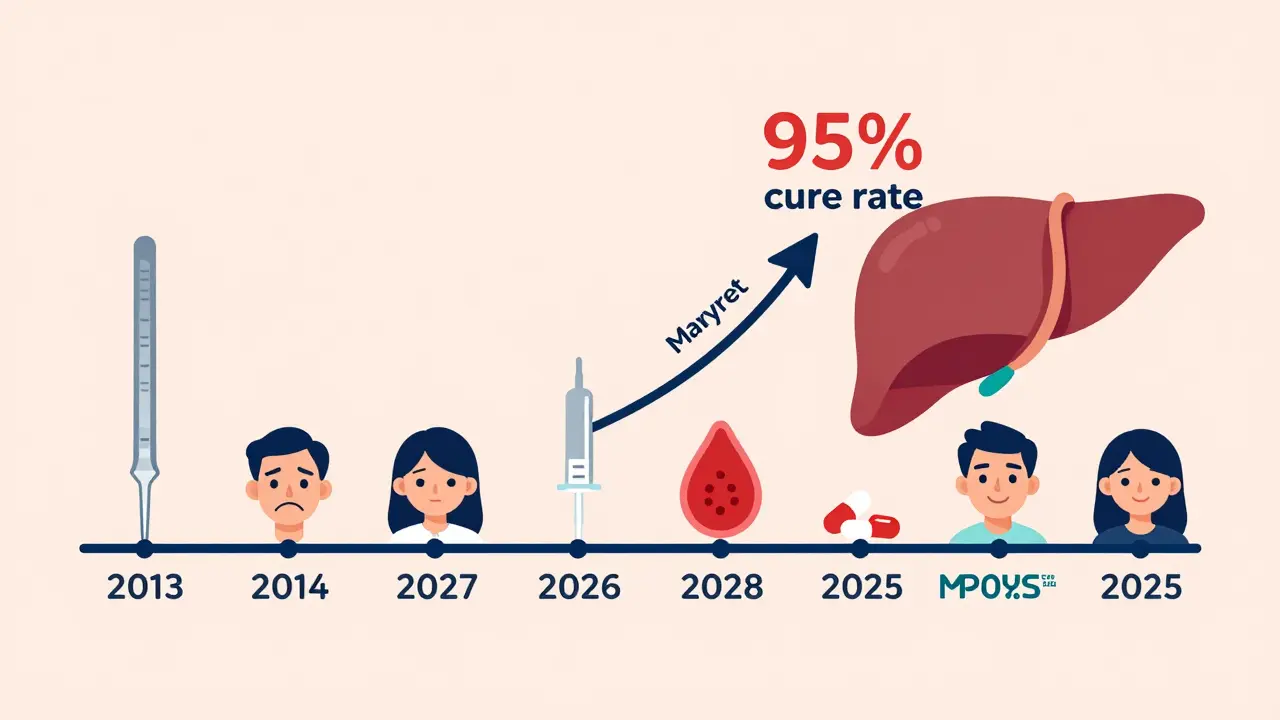

Before 2014, curing HCV meant months of injections, severe side effects, and low success rates. Today, it’s an 8- to 12-week pill regimen with almost no side effects. Drugs like glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret) and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa) clear the virus in over 95% of cases across all genotypes. These are not experimental. They’re standard, FDA-approved, and backed by years of real-world data. What’s new? Shorter treatments. The PURGE-C trial showed that just 4 weeks of Mavyret cured 84% of people with early (acute) HCV infection. That’s not quite as high as the 96% seen with 8 weeks, but for someone who can’t make it back for follow-ups, it’s a game-changer. And here’s the kicker: if the 4-week course doesn’t work, it doesn’t ruin your chances for longer treatment later. The virus doesn’t become resistant. You can just try again. In June 2025, the FDA officially approved Mavyret for acute HCV-the first and only DAA with that label. This isn’t just paperwork. It’s a signal that medicine is finally catching up to the reality that people need fast, simple options.Who’s at Highest Risk for Reinfection?

Not everyone gets reinfected. The risk isn’t random. It’s tied to behavior and access. - People under 30 are at higher risk-likely because they’re more likely to be actively injecting and less likely to have stable housing or healthcare access. - Ongoing drug use raises the risk 3.2 times. That’s not because they’re "unmotivated." It’s because they’re exposed to contaminated needles daily. - Methamphetamine users have 2.8 times higher risk. The drug increases risky behaviors and reduces self-care. - The first six months after cure are the most dangerous. That’s when people may feel safe, stop using harm reduction tools, or lose contact with clinics. The HERO study tracked these patterns across thousands of people. The data doesn’t lie: reinfection isn’t about moral failure. It’s about environment.

Harm Reduction Isn’t Optional-It’s Essential

You can’t cure HCV without addressing how people get infected. That’s where harm reduction comes in. It’s not about encouraging drug use. It’s about saving lives while people are working on their recovery. - Needle and syringe programs (NSPs) that give out at least 200 needles per person per year reduce HCV transmission by 54%. That’s not a guess. It’s a meta-analysis of 17 studies. - Opioid agonist therapy (OAT)-like methadone or buprenorphine-cuts HCV risk by half. When people are stable on medication, they’re less likely to share needles. - Co-locating HCV treatment with addiction services increases adherence by 82%. In Boston, clinics that offered Mavyret on the same day as methadone saw more people complete treatment than those who had to travel to separate clinics. Yet, a 2024 survey of 1,200 PWID found that 68% had been denied HCV treatment because they were still using drugs. That’s not medical ethics. That’s discrimination dressed up as policy.What Retreatment Looks Like Today

If you get HCV again, here’s what your doctor should do:- For reinfection (new exposure after cure): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret). No ribavirin needed. No resistance testing required.

- For relapse (virus came back after treatment): 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (Vosevi), or 16 weeks of Mavyret plus ribavirin. Resistance testing (NS3/NS5A sequencing) is recommended here.

What You Need to Do After Cure

Getting cured is a huge win. But it’s not the finish line.- Get tested for HCV RNA every 3 months for the first 6 months after cure. That’s when reinfection is most likely.

- Use sterile needles every time. Even one reused needle can spread HCV.

- Ask for OAT if you’re using opioids. It’s not giving up-it’s protecting your liver.

- Find a provider who treats you like a person, not a statistic. If they refuse care because you’re still using drugs, find someone else.

- Get tested for hepatitis B before starting any HCV treatment. HCV drugs can reactivate HBV, and that’s dangerous.

Why This Matters Beyond the Individual

Every person cured of HCV is a step toward ending the epidemic. But if we only treat people who don’t use drugs, we’ll never eliminate HCV. Mathematical models show that to reach WHO’s 2030 goal of 90% reduction in incidence, we need two things: more treatment and more harm reduction. Right now, only 38% of countries offer needle programs at recommended levels. That’s why global progress is stalled. The U.S. has made strides-20.4 million people treated since 2014-but we’re still leaving out the people who need it most. The truth? HCV elimination isn’t a medical challenge. It’s a moral one. We have the tools. We know what works. What’s missing is the will to give everyone equal access.What’s Next?

The NIH just launched PURGE-2, a trial testing a 2-week course of Mavyret for acute HCV. If it works-even at 75% success-it could revolutionize how we treat people in crisis. No clinic visits. No long waits. Just a short pill pack and a clean needle. Meanwhile, researchers are studying how the immune system recovers after cure. Turns out, if you had severe liver scarring before treatment, your immune system doesn’t bounce back fully. That means even after being cured, you still need regular liver checks. HCV is gone, but the damage might not be.Final Thought

Curing HCV isn’t about perfection. It’s about persistence. You might get infected again. You might need to be treated again. That’s okay. The goal isn’t to be flawless. The goal is to keep living. And with the right support, you can.Can you get hepatitis C again after being cured?

Yes. Being cured of HCV doesn’t give you immunity. If you’re still exposed to the virus-through sharing needles, unsterile equipment, or other blood-to-blood contact-you can get infected again. This is called reinfection, and it’s common among people who inject drugs. But it’s treatable. The same medications that cured you the first time work just as well the second time.

Is retreatment for HCV as effective as the first treatment?

Yes. Studies show retreatment success rates are just as high as initial treatment-over 95% with current direct-acting antivirals like Mavyret or Vosevi. Reinfection doesn’t make the virus harder to treat. What matters is getting the right drug combo for your situation, which your provider can determine.

Why do some doctors refuse to treat people who still use drugs?

Some providers still hold outdated beliefs that people must be "drug-free" to be treated. But that’s not supported by evidence. The CDC, WHO, and major medical societies all say HCV treatment should be offered to everyone, regardless of drug use. Refusing care based on substance use is stigma, not medicine. Many clinics now offer "treatment on demand" to remove these barriers.

How can harm reduction prevent HCV reinfection?

Harm reduction includes clean needle programs, opioid agonist therapy (like methadone), and education. Studies show that when people have access to 200+ sterile needles per year, HCV transmission drops by over 50%. When they’re on methadone or buprenorphine, their risk drops by half. These aren’t just add-ons-they’re essential parts of curing and preventing HCV.

How often should you get tested for HCV after being cured?

If you’re still at risk-like if you inject drugs or have ongoing exposure-you should get tested every 3 months for the first 6 months after cure. That’s when reinfection risk is highest. After that, testing every 6 to 12 months is recommended if risk continues. Regular testing catches reinfection early, so you can treat it quickly.

Are there shorter treatment options for HCV now?

Yes. For people with early (acute) HCV infection, an 8-week course of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret) is standard. But recent trials show a 4-week course can cure 84% of cases. A 2-week trial is now underway. Shorter treatments help people who struggle to stay in care-like those without stable housing or transportation.

Can HCV be cured without going to a specialist?

Yes. In many places, primary care providers, pharmacists, and even community health workers can prescribe and manage HCV treatment. You don’t need a liver specialist. The guidelines have shifted to make treatment simpler and more accessible. The key is having access to the right drugs and getting tested before and after treatment.