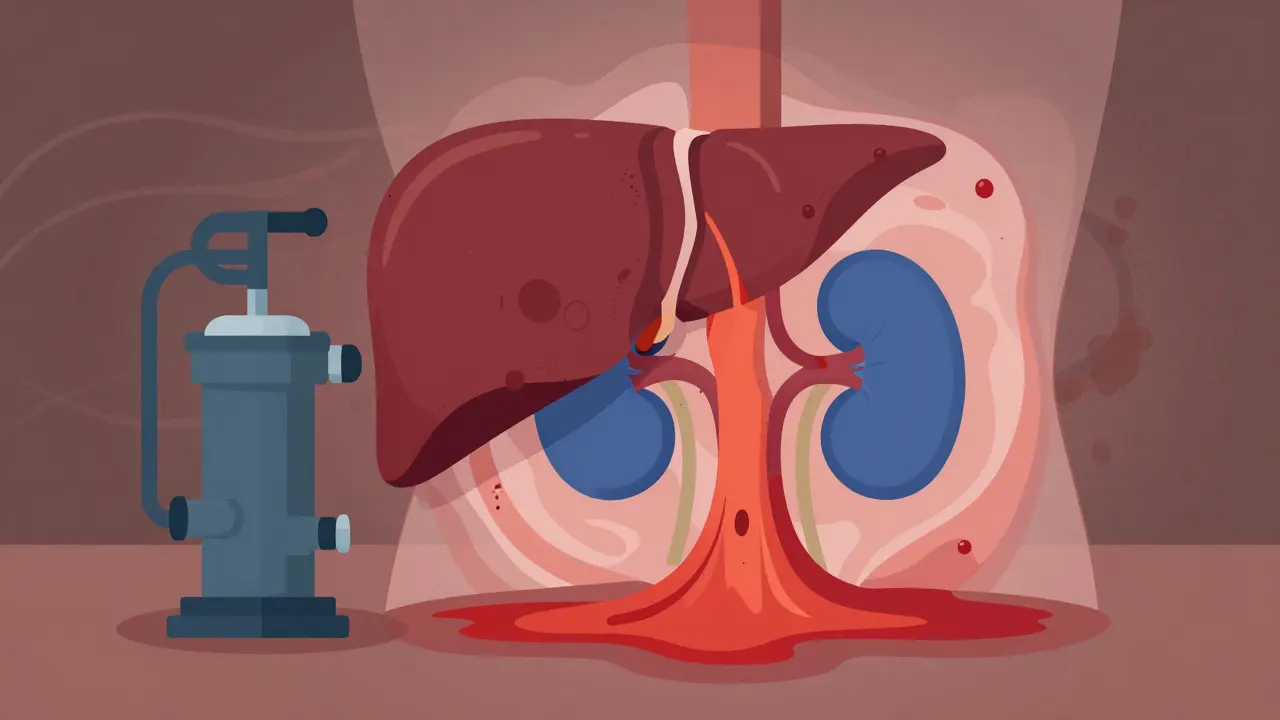

When your liver is failing, your kidneys don’t just slow down-they can shut down completely, even if they’re not damaged. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s hepatorenal syndrome, a deadly chain reaction triggered by advanced liver disease. Think of it like a broken water pump: the liver’s collapse messes up blood flow so badly that the kidneys stop working, even though they’re physically fine. This isn’t a slow decline. In its most aggressive form, kidney function can crash in days. And without treatment, survival is measured in weeks.

What Exactly Is Hepatorenal Syndrome?

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) isn’t kidney disease. It’s liver disease pretending to be kidney disease. People with cirrhosis-where scar tissue replaces healthy liver tissue-can develop HRS when their body’s circulation goes haywire. The liver can’t regulate blood pressure properly, so blood pools in the abdomen and intestines. The body thinks it’s drowning in fluid, so it tightens blood vessels everywhere, including in the kidneys. That’s the problem. The kidneys aren’t broken. They’re just starved of blood.

This isn’t guesswork. It’s been studied for decades. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the International Club of Ascites (ICA) have strict rules to diagnose it. You need to rule out every other possible cause of kidney failure: no kidney stones, no infection, no drug damage, no severe dehydration. If all those are gone and the kidneys still aren’t working in someone with advanced cirrhosis, you’re looking at HRS.

Two Types, Two Timelines

HRS doesn’t come in one flavor. It comes in two, each with its own speed and survival rate.

Type 1 HRS is a medical emergency. Creatinine-a waste product the kidneys filter-spikes to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. That’s a two-fold jump. Patients often go from feeling tired to needing dialysis in days. Median survival without treatment? Just two weeks. This type is often triggered by infections like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), which happens in 35% of cases. It’s also common after major bleeding or sudden alcohol binges.

Type 2 HRS moves slower. Creatinine stays between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL. It’s not as instantly life-threatening, but it’s just as dangerous over time. This type is almost always tied to refractory ascites-fluid in the belly that won’t go away, no matter how much diuretic you give. Patients might feel bloated for months, but their kidneys are quietly failing. Without a transplant, many will eventually slip into Type 1.

How Do Doctors Know It’s HRS?

Diagnosing HRS is like solving a puzzle with missing pieces. You can’t rely on a single test. You need a combination of clues:

- Serum creatinine above 1.5 mg/dL (in cirrhosis with ascites)

- Urine sodium under 10 mmol/L (kidneys are holding onto salt)

- Urine osmolality higher than blood (kidneys are trying to conserve water)

- No protein in urine or blood in urine (rules out kidney damage)

- No improvement after stopping diuretics and giving albumin for 48 hours

And here’s the kicker: a kidney biopsy will show nothing wrong. That’s what makes HRS unique. The organ isn’t damaged-it’s just being starved. That’s why so many patients get misdiagnosed. A 2020 audit found 25-30% of HRS cases were mistaken for other types of kidney failure. That leads to the wrong treatment, and worse outcomes.

What Triggers It?

It’s not just cirrhosis. Something has to push the system over the edge. The most common triggers:

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) - 35% of cases

- Upper GI bleeding - 22%

- Acute alcoholic hepatitis - 11%

- Overuse of diuretics or NSAIDs

- Large-volume paracentesis without albumin replacement

SBP is the biggest red flag. If someone with cirrhosis suddenly gets fever, abdominal pain, or confusion, HRS could be right around the corner. That’s why antibiotics are given immediately-not just to treat the infection, but to prevent kidney failure from following.

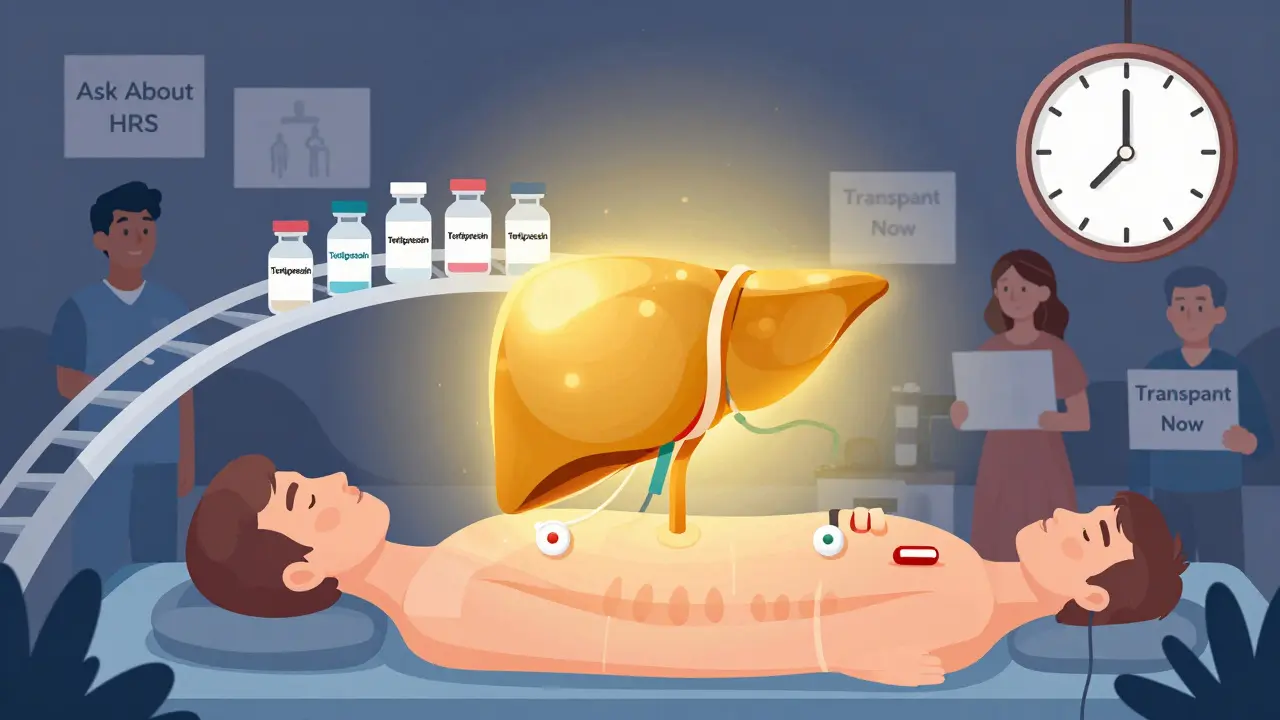

What Treatments Actually Work?

There’s no magic pill. But there are treatments that save lives-if used fast enough.

The gold standard for Type 1 HRS is terlipressin plus albumin. Terlipressin is a drug that tightens blood vessels, redirecting blood flow back to the kidneys. Albumin helps hold fluid in the bloodstream so the kidneys aren’t overwhelmed. Together, they work in about 44% of cases, bringing creatinine down below 1.5 mg/dL within two weeks. But it’s not easy. Side effects include severe abdominal cramps, low blood pressure, and even heart rhythm problems. One patient reported needing to cut their dose in half just to tolerate it.

In the U.S., terlipressin got FDA approval in December 2022 under the brand name Terlivaz™. But it costs about $1,100 per vial. A full 14-day course? Around $13,200. Many insurance companies still fight coverage, even when the criteria are met. That’s why some patients still get compounded versions-cheaper, but less reliable.

For Type 2 HRS, doctors sometimes use midodrine and octreotide together. These are oral drugs that also constrict blood vessels. But they’re less effective. One patient on Reddit said their husband didn’t respond after six weeks. His MELD-Na score (a measure of liver disease severity) hit 28-high enough to get priority on the transplant list.

The Only Real Cure: Transplant

Medications can buy time. But the only cure for HRS is a liver transplant.

Without a transplant, only about 18% of Type 1 HRS patients survive a year. With terlipressin and albumin? That jumps to 39%. But with a transplant? It’s 71%. That’s not a slight improvement-it’s a life-or-death difference.

That’s why experts now say: if you have Type 1 HRS, get on the transplant list immediately. You don’t need to wait for kidney function to improve. The 2023 European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA) guidelines say listing should happen right away. Why? Because the longer you wait, the more likely you’ll develop complications that make transplant riskier.

And the system is adapting. Since 2022, the MELD-Na score-which determines transplant priority-has been adjusted to give more weight to kidney function. That means HRS patients now move up the list faster. In some centers, transplant wait times have dropped by weeks.

Why So Many Patients Are Left Behind

Here’s the ugly truth: most people with HRS never get the right care.

A 2022 survey of 312 patients and caregivers by the Global Liver Institute found:

- 78% waited over a week for diagnosis

- 63% were misdiagnosed at least once

- 41% had insurance deny terlipressin

Even in the U.S., only 35% of hospitals have a formal HRS protocol. Most community hospitals don’t know how to test for it. They see high creatinine, assume it’s kidney failure, and start dialysis. But dialysis doesn’t fix HRS. It just masks the real problem: the liver.

And it’s worse globally. In sub-Saharan Africa, 89% of HRS patients get only supportive care-fluids, maybe a diuretic. No terlipressin. No transplant. No chance.

What’s Next? Hope on the Horizon

Research is moving fast. Scientists are testing new biomarkers like NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) to catch HRS before it hits. One trial is looking at a cutoff of 0.8 ng/mL in urine-early enough to intervene before creatinine rises.

Other drugs are in trials: PB1046, a new vasopressin agonist, and the alfapump®, a device that drains fluid from the belly automatically. These could help Type 2 patients avoid the downward spiral.

But none of this matters if we don’t fix the system. HRS isn’t rare. It affects up to 40% of people with end-stage liver disease. And yet, it’s still underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underfunded. The tools exist. The guidelines are clear. What’s missing is the will to use them.

What You Can Do

If you or someone you love has cirrhosis:

- Know the signs: sudden swelling, less urine, confusion, fatigue

- Ask your doctor: “Could this be hepatorenal syndrome?”

- Insist on albumin after large fluid draws

- Get tested for infections like SBP

- Ask about transplant evaluation-don’t wait for kidney failure to get worse

Hepatorenal syndrome doesn’t care how smart you are or how much you know. It only cares if you act fast. The window is small. But it’s not closed.

Is hepatorenal syndrome the same as kidney disease?

No. Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is not kidney disease. It’s a functional kidney failure caused by advanced liver disease. The kidneys themselves aren’t damaged-they just stop working because blood flow is redirected away from them due to severe liver dysfunction. A kidney biopsy will show normal tissue, which is why HRS is often misdiagnosed as acute kidney injury.

Can hepatorenal syndrome be reversed without a transplant?

Yes, in some cases. Type 1 HRS can be reversed with terlipressin and albumin, which improves kidney function in about 44% of patients. Type 2 HRS may respond to midodrine and octreotide, especially if ascites is controlled. But these treatments only stabilize the condition. Without a liver transplant, most patients will eventually relapse or progress to more severe kidney failure.

What’s the difference between Type 1 and Type 2 HRS?

Type 1 HRS is rapid and life-threatening: creatinine doubles to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. It’s often triggered by infection or bleeding and requires urgent treatment. Type 2 HRS is slower, with creatinine between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL. It’s usually linked to refractory ascites and doesn’t progress as quickly, but it often leads to Type 1 if untreated. Survival is longer with Type 2, but both types require transplant for a cure.

Why is terlipressin so expensive?

Terlipressin was approved in the U.S. in December 2022 under the brand name Terlivaz™. It costs about $1,100 per 1mg vial. A standard 14-day course requires 12 vials-totaling around $13,200. The price is high because it’s a newly approved drug with limited competition. Before approval, many hospitals used compounded versions, which were cheaper but less consistent. Insurance companies often deny coverage, even when guidelines support use, creating access barriers for patients.

Can you survive hepatorenal syndrome without a transplant?

Survival without a transplant is poor. For Type 1 HRS, median survival without treatment is just two weeks. With terlipressin and albumin, 1-year survival improves to about 39%. But without transplant, most patients relapse within months. Type 2 HRS has a longer course, but 1-year survival without transplant is still under 25%. Liver transplant remains the only definitive cure, with 1-year survival rates of 71% or higher.

How can I prevent hepatorenal syndrome if I have cirrhosis?

You can’t always prevent it, but you can reduce your risk. Avoid NSAIDs (like ibuprofen) and excessive diuretics. Get vaccinated for pneumonia and flu to prevent infections. If you have ascites, always get albumin after a large fluid draw. Treat infections like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis immediately. And get evaluated for liver transplant early-before kidney function starts to decline.