When a patient walks up to the counter with a prescription for brand-name medication, the pharmacist doesn’t just hand over the first thing that looks similar. There’s a legal process. A set of rules. And if those rules aren’t followed exactly, the consequences can be serious-fines, license suspension, even lawsuits. The stakes are high because what seems like a simple swap-brand to generic-can actually affect a patient’s health in ways that aren’t always obvious.

What Exactly Counts as a Generic?

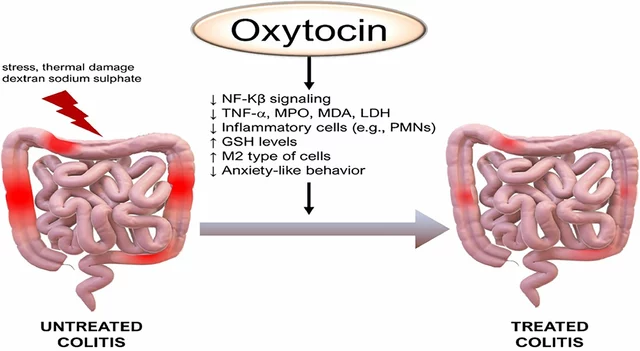

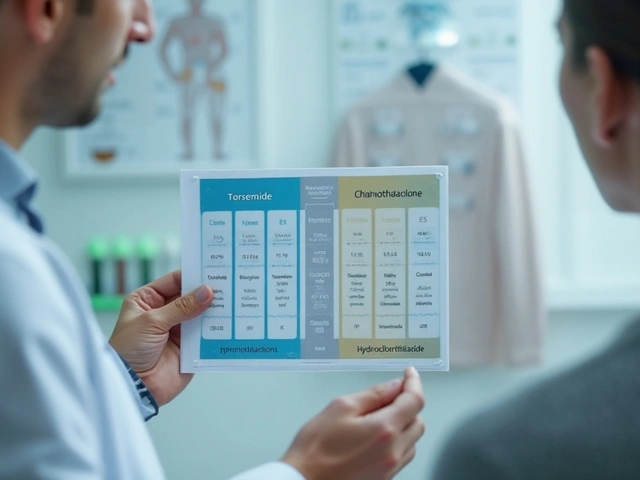

A generic drug isn’t just a cheaper copy. It’s a scientifically proven equivalent. The FDA requires that generics have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also be bioequivalent-that means they work the same way in the body, with no meaningful difference in how fast or how much of the drug gets absorbed. This isn’t theory. It’s tested in clinical studies before approval. The FDA’s Orange Book lists every approved generic and its therapeutic equivalence rating. Only A-rated drugs are considered interchangeable without clinical concern.State Laws Are Not the Same

Here’s where it gets complicated. There’s no single federal rule that tells pharmacists when they must, can, or can’t substitute. Instead, each of the 50 states and Washington D.C. has its own law. That means a pharmacist in New York has different obligations than one in Florida, even if they’re filling the same prescription. Some states are mandatory substitution states. That means if a generic is available and the prescription doesn’t say “dispense as written,” the pharmacist must substitute it. That’s true in 24 states as of 2023. Other states are permissive-pharmacists can substitute, but aren’t required to. In those places, the decision is up to professional judgment. But it doesn’t stop there. Some states require explicit patient consent before substitution. That means the pharmacist has to tell the patient, get a clear “yes,” and document it. That’s the case in 32 states. In 18 others, consent is presumed-unless the patient says no, substitution can happen. That creates a huge difference in how the conversation plays out at the counter.Drugs That Can’t Be Substituted

Not every drug is fair game. Even if a generic has an A rating, some medications are off-limits for substitution in certain states. The most common exceptions involve drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where even tiny changes in blood levels can cause harm. Antiepileptic drugs are a big one. Tennessee, Hawaii, and a few others ban substitution for epilepsy patients unless the prescriber specifically allows it. Why? Because a 10% drop in blood concentration might trigger a seizure. Even if the generic meets FDA standards, the risk is too real for some patients. Other high-risk categories include:- Anticoagulants like warfarin

- Cardiac glycosides like digoxin

- Anti-asthmatic inhalers, especially time-release forms

- Thyroid medications like levothyroxine

- Insulin

The Pharmacist’s Legal Duty

Pharmacists aren’t just order-fillers. They’re the last line of defense. That means checking three things every single time:- Is the generic approved by the FDA and rated A in the Orange Book?

- Does the prescription have a “dispense as written” or “medically necessary” notation?

- Does state law require patient consent, and was it obtained properly?

When Patients Push Back

Patients don’t always understand why a generic isn’t allowed. One Reddit user shared a story about a Tennessee pharmacist who substituted an antiepileptic drug because they didn’t know the state’s exception. The patient had a seizure. Emergency intervention followed. That’s not hypothetical. That’s real. On the flip side, patients love generics. AARP’s 2022 survey found patients save an average of $38.50 per prescription when switching. But 63% of negative reviews on health sites cite “no notification” as the main complaint. Patients feel tricked when they don’t know what they’re getting. That’s why counseling matters. A quick, clear explanation-“This is a generic version of your medication. It’s the same active ingredient, approved by the FDA, and costs less. Your doctor approved the switch.”-can turn frustration into trust. If substitution isn’t allowed, say why: “State law doesn’t let us switch this one because it’s for seizure control and small changes can be risky.”

What Happens When You Get It Wrong?

A mistake isn’t just a bad day at work. It can mean:- A state board investigation

- Fines up to $10,000 per violation

- License suspension or revocation

- Civil lawsuits if harm occurs

What’s Changing in 2026?

The landscape keeps shifting. In 2022, Congress passed a law requiring new labeling on all generic drugs to help patients understand substitution. That took effect in late 2024. Now, generics must clearly state they are “therapeutically equivalent” and include a brief note about cost savings. Biosimilars-complex biologic drugs that aren’t technically generics-are also entering the picture. Thirty-two states have passed laws allowing substitution of these drugs, but the rules are different. They require additional documentation and often require prescriber approval. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is pushing for a model law to standardize rules across states. So far, 14 states have adopted parts of it. But until there’s full national alignment, pharmacists must still treat each state like a different country.Bottom Line: Know the Law, Document Everything

Dispensing generics isn’t about saving money. It’s about following the law while protecting patient safety. The system works because pharmacists act as gatekeepers-not just technicians. Every substitution requires a checklist: FDA rating, prescriber instructions, state consent rules, patient communication, and documentation. There’s no room for guesswork. If you’re unsure, don’t substitute. Call the prescriber. Check your state’s pharmacy board website. Ask a colleague. Better to delay a fill than risk a patient’s health-or your career.Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $300 billion a year. But that savings only works if every step is done right. And that starts with the pharmacist at the counter.

Can a pharmacist substitute a generic without telling the patient?

It depends on the state. In 32 states, pharmacists must get explicit consent before substituting a generic. In the other 18, consent is presumed-meaning substitution can happen unless the patient says no. But even in presumed consent states, many pharmacies still notify patients as a best practice to avoid complaints or confusion.

Are all generics safe to substitute?

Not all. The FDA approves generics as bioequivalent, but state laws restrict substitution for certain drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes-like warfarin, digoxin, levothyroxine, and antiepileptics. Even if a generic is rated ‘A,’ it may be legally prohibited from being swapped in some states. Always check your state’s formulary and restrictions.

What if the prescriber writes ‘dispense as written’?

That overrides any state substitution law. If the prescriber clearly indicates the brand must be dispensed-whether by writing “DAW 1,” “dispense as written,” or checking a box on an e-prescription-the pharmacist cannot substitute, no matter what the state allows. This is a legal requirement, not a suggestion.

Do pharmacists need special training to dispense generics?

Yes. Most states require continuing education on generic substitution laws. Pharmacists must stay current because laws change frequently-17 states updated their rules in 2022 alone. Training includes understanding the FDA Orange Book, state-specific consent rules, formulary restrictions, and proper documentation. Many pharmacists spend 40-60 hours per year on this topic alone.

Can a pharmacist be held liable if a patient has a bad reaction to a generic?

Yes. If the pharmacist substituted a drug that was legally prohibited, failed to obtain required consent, or ignored a “dispense as written” order, they can be held liable-even if the generic was FDA-approved. A 2023 study showed 12.7% higher adverse events in some patients after switching cardiac glycosides, and courts have ruled pharmacists responsible when substitution protocols weren’t followed.

How do I know if a generic is approved for substitution?

Use the FDA’s Orange Book, which is updated monthly. Look for the therapeutic equivalence code. Only drugs rated ‘A’ are considered interchangeable. ‘B’ rated drugs are not approved for substitution. Most pharmacy software pulls this data automatically, but pharmacists should verify it manually when dealing with high-risk medications.

13 Comments

Erwin Kodiat

January 20, 2026 AT 01:38 AM

Love that this post breaks it down so clearly. Honestly, I didn’t realize how wild the state-by-state stuff is. I thought generics were just ‘same drug, cheaper’-turns out it’s like navigating 50 different rulebooks.

Big respect to pharmacists who actually keep up with this. Most people don’t even know what ‘A-rated’ means.

Lewis Yeaple

January 20, 2026 AT 23:53 PM

It is imperative to underscore that the FDA’s bioequivalence standards, while statistically robust, do not account for inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability. A 90% confidence interval for Cmax and AUC is not synonymous with clinical equivalence across all patient populations.

Furthermore, the therapeutic index of drugs such as levothyroxine and digoxin renders even minor deviations in absorption-often attributable to excipient differences-potentially catastrophic. The regulatory framework is fundamentally inadequate for high-risk pharmacotherapeutics.

Tracy Howard

January 22, 2026 AT 18:42 PM

Oh wow, so Americans can’t even agree on what a pill is? You’ve got 50 different versions of ‘pharmacy law’ like some kind of federalist nightmare?

Meanwhile, Canada just says ‘if it’s FDA-approved and the script doesn’t say otherwise, swap it and tell the patient.’ No drama. No paperwork. No lawsuits.

Y’all are turning a simple generic swap into a constitutional crisis. It’s embarrassing.

Jake Rudin

January 24, 2026 AT 10:49 AM

It’s not about the drug… it’s about the system.

Why do we let profit dictate safety? Why is the pharmacist-the only licensed professional left who actually touches the medicine-burdened with 32 different consent forms, 18 presumed-consent loopholes, and a 200-page state formulary they’re expected to memorize?

We’ve outsourced medical judgment to spreadsheets and software, then blamed the pharmacist when the algorithm fails.

And yet, we still expect them to be the emotional anchor for patients who just got hit with a $1200 bill for a brand name… and then wonder why they’re burnt out.

The real problem isn’t substitution.

It’s a healthcare system that treats people like cost centers.

Lydia H.

January 26, 2026 AT 01:12 AM

My grandma takes levothyroxine. She switched to generic once and got dizzy for three weeks. We went back to brand, and boom-she was fine.

She didn’t know the difference. Neither did the pharmacist. They just swapped it because the insurance said so.

It’s scary how many people are just… guessing. And nobody’s talking about it.

Thanks for making this so clear. I’m sending this to my state rep.

Valerie DeLoach

January 27, 2026 AT 14:14 PM

As a pharmacist for 18 years, I can confirm: documentation is everything. I’ve seen cases where patients swear they were never told about a switch-only to find the consent form signed and dated, but buried in a digital chart no one ever checks.

Here’s the truth: most pharmacists want to do right by patients. But we’re drowning in bureaucracy. We’re expected to be legal experts, counselors, and tech support for EHRs-all while managing 120 prescriptions an hour.

Training isn’t optional. It’s survival.

And yes-we do know the Orange Book inside out. But if your state’s law changed last month and the software hasn’t updated? That’s on the state. Not us.

Christi Steinbeck

January 28, 2026 AT 12:12 PM

STOP acting like generics are dangerous. They’re not. The system is broken. Pharmacists aren’t the villains-insurance companies are.

I’ve had patients cry because their $3 generic got denied and they had to pay $400 for brand. Then the pharmacist swaps it anyway, gets reported, and gets audited.

We need to fix the insurance rules, not punish the people trying to help.

Also-yes, some drugs are high-risk. But don’t use that to scare people out of saving money. Educate. Don’t demonize.

Jackson Doughart

January 28, 2026 AT 22:41 PM

There’s a quiet dignity in the work pharmacists do that never makes the headlines.

They’re the last human checkpoint before a drug enters your body. They know the risks, the laws, the exceptions. And yet, they’re treated like order-takers.

When I got my warfarin switched without consent, I didn’t blame the pharmacist. I blamed the system that made it possible.

Let’s honor the people who show up every day to do the right thing-when no one’s watching.

Malikah Rajap

January 30, 2026 AT 21:14 PM

Wait-so if I’m in a state with presumed consent, and I don’t say anything, they can swap my meds… even if I’m 80 and have 12 prescriptions? And I’m supposed to just… notice the difference? And then what? Go back and complain? After I’ve had a stroke?

That’s not consent. That’s negligence dressed up as efficiency.

Also-why do pharmacies even have formularies? Isn’t that the doctor’s job?

Someone’s getting paid to make this complicated… and it ain’t the pharmacist.

sujit paul

February 1, 2026 AT 02:07 AM

This is all part of the New World Order pharmaceutical control system. The FDA and Big Pharma collude to push generics, which contain undisclosed fillers that alter neural pathways. The state laws are designed to confuse the public while the real agenda-mind control via bioequivalent toxins-is hidden behind bureaucratic jargon.

Check the Orange Book. You’ll see the same manufacturer codes appear in NSA surveillance contracts. Coincidence? I think not.

Aman Kumar

February 2, 2026 AT 10:10 AM

Let me be unequivocal: the current paradigm of generic substitution is a pharmacological farce. The excipients-microcrystalline cellulose, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate-are not inert. They induce epigenetic modulation in susceptible populations, particularly those with polymorphisms in CYP2D6 and CYP2C19.

Moreover, the FDA’s bioequivalence thresholds are based on healthy young males-ignoring the elderly, the obese, and the polypharmacy cohort.

What you call ‘A-rated’ is, in clinical reality, a statistical illusion with lethal consequences.

And yet, the pharmacy boards remain complicit.

Astha Jain

February 2, 2026 AT 22:46 PM

generic are fine but why do they never tell u?? i got my thyroid med swapped and felt like a zombie for a week and no one said a word. like… i dont even know what i took. so rude.

Josh Kenna

January 18, 2026 AT 20:52 PM

Man, I had a pharmacist swap my seizure med last year and I ended up in the ER-turns out they didn’t know Tennessee bans it. No warning, no consent, just a cheaper pill. That’s not healthcare, that’s Russian roulette with your brain.

Pharmacists need to stop acting like they’re just cashiers. This isn’t a grocery run.