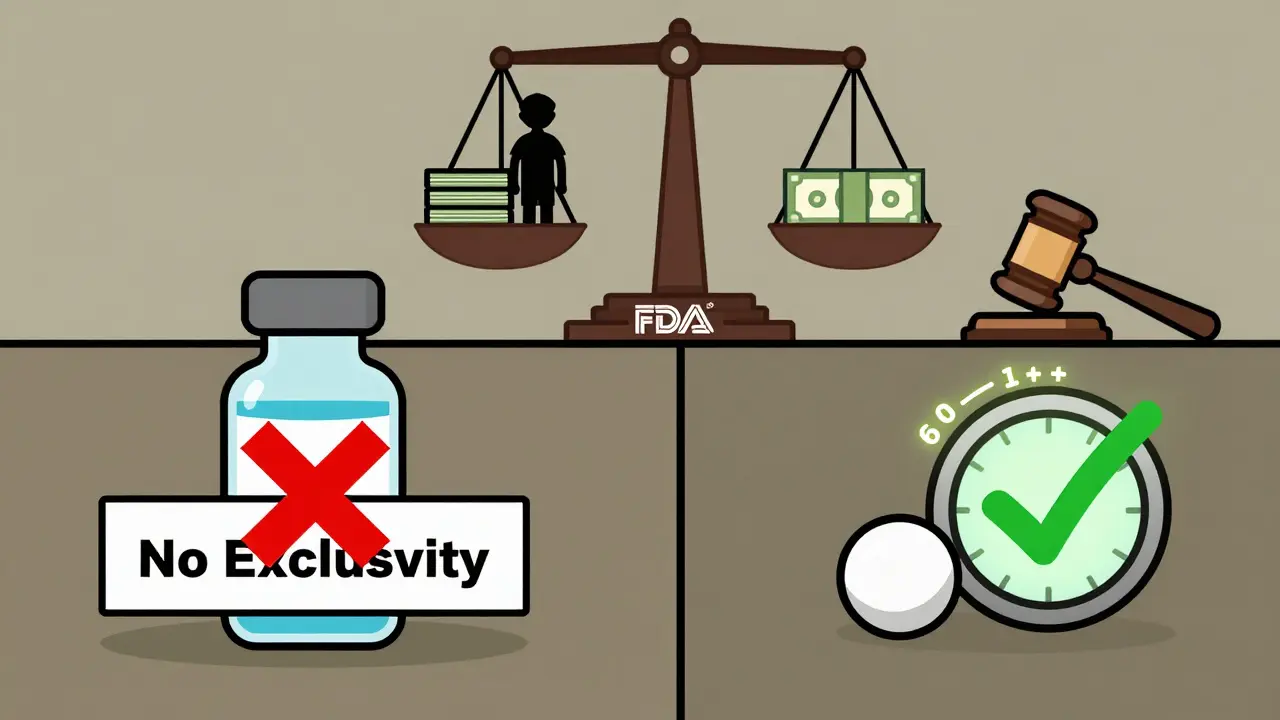

When a drug company gets FDA approval for a new medicine, it doesn’t just get a green light-it gets a clock. That clock runs on patents and exclusivity periods, and for many blockbuster drugs, the six-month extension from pediatric exclusivity can mean hundreds of millions in extra revenue. But here’s the twist: pediatric exclusivity doesn’t actually extend the patent. It extends the FDA’s ability to approve generic versions. It’s not about the patent clock. It’s about the approval clock.

What Pediatric Exclusivity Really Does

Pediatric exclusivity is a six-month bonus granted by the FDA under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. It’s not a patent. It’s not a new law. It’s a regulatory tool designed to fix a real problem: drugs were being given to kids without proper studies. Doctors had no idea what dose to use. Side effects were unknown. So Congress created an incentive: do the pediatric studies, and you get six more months of market protection.

That protection doesn’t change the patent’s expiration date. Instead, it blocks the FDA from approving any generic version-whether it’s an ANDA or a 505(b)(2) application-until that six-month window closes. Even if the patent has already expired, the FDA still can’t approve a generic unless the exclusivity period ends. That’s why it’s so powerful. A drug with no patent left? Still protected. A generic ready to launch? Still blocked.

How It Works: The Written Request System

The FDA doesn’t just hand out pediatric exclusivity. You have to earn it. The process starts with a Written Request. This is a formal document from the FDA telling a drug company: "Here’s what we need you to study in children." It might be a new age group, a different dosage form, or a new indication. The request is specific: which population, what endpoints, what study design.

The company then conducts the studies, submits the data, and the FDA has 180 days to review whether it meets the requirements. If it does, pediatric exclusivity kicks in. No need for a new drug application. No need to change the label. Just submit the studies, and the clock extends.

What’s surprising? You don’t even need to change the label. The exclusivity attaches as soon as the FDA accepts the study reports. That’s why it’s so valuable-it’s not tied to approval. It’s tied to submission.

Who Gets It? And Who Doesn’t?

Pediatric exclusivity applies to all dosage forms and indications of the same active ingredient. If a company has an oral tablet, a liquid, and an injection-all with the same active moiety-and they study one of them in kids, the six-month extension applies to all three. That’s a huge multiplier. One study, six months across every version of the drug.

But here’s the catch: the drug must still have some form of existing exclusivity or patent protection. If a drug’s five-year new chemical entity exclusivity expired two years ago, and there’s no patent left, pediatric exclusivity won’t apply-unless the supplemental application itself qualifies for a new exclusivity period. For example, if a company applies to extend an adult-only drug to children and needs new clinical data to do it, that new application can trigger a fresh exclusivity period, which then allows pediatric exclusivity to attach.

Biologics? Not covered. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) doesn’t have the same patent linkage system as the Hatch-Waxman Act. So even if a biologic maker does pediatric studies, they get no extra exclusivity. That’s a major gap in the system.

The Real Impact: When Patents Expire

Most people think patent expiration means generics can rush in. Not always. Pediatric exclusivity can block them even after the patent dies. That’s where things get tricky.

Imagine a drug with a patent expiring on June 30, 2025. The company did pediatric studies and got exclusivity. That exclusivity runs until December 30, 2025. Even though the patent is gone, the FDA still can’t approve a generic until December 30. Generic companies can file their applications on July 1, but the FDA holds them until the exclusivity period ends.

And here’s the legal nuance: if a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification (challenging the patent), and wins in court, the FDA can approve the generic-even during pediatric exclusivity. But if the patent is expired and the generic files a Paragraph II certification (no patent), pediatric exclusivity becomes the only barrier. Courts have upheld the FDA’s right to treat these as Paragraph II applications after patent expiry, meaning exclusivity stands alone.

Strategic Value: Why Companies Chase It

For a drug that brings in $1 billion a year, six months of exclusivity equals $500 million in extra revenue. That’s why companies invest millions in pediatric studies-even when the pediatric market is small. The return on investment is massive.

It’s also used as a lifecycle management tool. A company might let a patent expire, then file a supplemental application for a new pediatric indication. That triggers a new three-year exclusivity period, and then pediatric exclusivity adds six more months. Suddenly, you’ve extended market protection for nearly three years without a new patent.

Even formulation patents can get pulled in. If a company gets a new patent on a delivery system-say, a delayed-release version-after the original patent expires, pediatric exclusivity still extends that new patent’s effect. The FDA treats it as part of the same product family.

What Blocks Pediatric Exclusivity

It’s not foolproof. There are three main ways a generic can get through:

- Waiver from the brand company-rare, but sometimes negotiated.

- Court ruling-if a judge says the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed.

- Failure to sue-if the brand company doesn’t sue within 45 days of the Paragraph IV notice, the generic can launch without waiting for exclusivity to expire.

And here’s something many overlook: pediatric exclusivity doesn’t apply if the drug is already off-patent and no new exclusivity is triggered. That’s why timing matters. A single day can make the difference between getting the extension or losing it.

The Bigger Picture

Pediatric exclusivity was never meant to be a profit engine. It was meant to protect kids. And it worked. Before 1997, only about 20% of drugs had pediatric labeling. Today, it’s over 80%. That’s a win.

But the system has evolved. What started as a public health tool became a strategic lever in pharmaceutical business. Companies now plan their entire lifecycle around it. They time their studies, their patent filings, their applications-all to squeeze out every possible month of exclusivity.

And the FDA? It plays its part with precision. It doesn’t just approve studies. It enforces the rules. It tracks every patent, every exclusivity period, every application. And it doesn’t budge unless the law says so.

For generic manufacturers, it’s a maze. For brand companies, it’s a lifeline. And for kids? It’s the reason they now get safer, better-dosed medicines.

What’s Next?

There’s no sign pediatric exclusivity is going away. In fact, the FDA has been more active than ever in issuing Written Requests. The 2023 Pediatric Exclusivity Report showed over 70 requests issued that year alone. And with more drugs being developed for rare pediatric diseases, the demand for these studies is growing.

But the debate continues. Should pediatric exclusivity be limited to drugs with high pediatric use? Should it be tied to actual pediatric labeling changes? Should it apply to biologics? These are open questions.

For now, the system stands. Six months. One rule. One goal: better data for children. And for drug companies? A powerful, legally ironclad extension that doesn’t need a patent to work.

Does pediatric exclusivity extend the actual patent term?

No. Pediatric exclusivity does not extend the patent’s legal expiration date. Instead, it delays the FDA from approving generic versions of the drug for six months, even if the patent has already expired. It’s a regulatory barrier, not a patent extension.

Can a drug get pediatric exclusivity if it has no patents left?

Only if the supplemental application for the pediatric use qualifies for a new exclusivity period. For example, if a company adds a new pediatric indication and needs new clinical data to get approval, that application can trigger a new three-year exclusivity period, which then allows pediatric exclusivity to attach.

Does pediatric exclusivity apply to biologics?

No. Pediatric exclusivity only applies to small-molecule drugs regulated under the Hatch-Waxman Act. Biologics are governed by the BPCIA, which does not include patent linkage or pediatric exclusivity provisions.

How long does the FDA take to review pediatric study reports?

The FDA has 180 days to review whether the pediatric studies meet the requirements of the Written Request. Once accepted, pediatric exclusivity is granted and applies retroactively to the date the studies were submitted.

Can a generic drug be approved during pediatric exclusivity?

Yes, but only under three conditions: if the brand company grants a waiver, if a court rules the patent invalid or not infringed, or if the brand company fails to sue within 45 days of a Paragraph IV notice. Otherwise, the FDA cannot grant final approval until the exclusivity period ends.

Does pediatric exclusivity apply to all dosage forms of a drug?

Yes. If a company studies one dosage form (like an oral tablet) and receives pediatric exclusivity, the six-month protection applies to all other dosage forms (liquid, injection, cream, etc.) that contain the same active moiety, as long as they have remaining exclusivity or patent protection.

Is pediatric exclusivity worth the cost for drug companies?

For blockbuster drugs, yes. A six-month exclusivity extension can generate hundreds of millions in additional revenue. Even for drugs with smaller markets, the ability to delay generic competition often justifies the cost of pediatric studies, especially when the exclusivity applies across all formulations and indications.

8 Comments

Alexandra Enns

January 24, 2026 AT 14:24 PM

Oh please. Canada doesn’t even have this system and we still get safe pediatric meds. The U.S. is just addicted to corporate handouts disguised as public health. This isn’t progress-it’s legalized greed wrapped in a lab coat. 🇨🇦 > 🇺🇸

asa MNG

January 25, 2026 AT 10:49 AM

so like… if the patent is dead but this exclusivity thing is still going… its like the FDA is holding the keys to the car but the owner just died? 😅 i mean wtf. why cant generics just roll in? also i think i saw a tweet that said biologics are getting left behind and thats kinda wild bc kids get biologics too for cancer and shit

Sushrita Chakraborty

January 26, 2026 AT 08:44 AM

It is truly commendable that the FDA has implemented this mechanism to ensure that pediatric populations are not subjected to off-label use without adequate clinical data. The six-month exclusivity period, while economically advantageous to manufacturers, has demonstrably improved the safety profile of medications administered to children. In India, where access to pediatric pharmacology data remains inconsistent, such regulatory frameworks serve as a vital benchmark.

Josh McEvoy

January 27, 2026 AT 18:38 PM

so wait… you’re telling me companies just do one tiny study on kids and then get 6 months of monopoly on EVERY FORM of the drug?? like… the liquid, the spray, the patch?? 🤯 that’s insane. also why does the FDA even care if the patent’s expired?? this feels like a loophole designed by a lawyer who hates competition

Heather McCubbin

January 27, 2026 AT 19:26 PM

Let’s be real this isn’t about kids it’s about money. They’re playing chess with the lives of children’s health and calling it science. The FDA is just the puppet. The real winners? The CEOs who cash in on the suffering of parents who can’t afford brand-name meds. This system is a cancer on healthcare and nobody’s willing to cut it out because the money’s too big

Sawyer Vitela

January 29, 2026 AT 05:37 AM

Patent expired. Exclusivity still active. FDA blocks generics. Legal. No court challenges. That’s the system. No drama. Just math.

Shanta Blank

January 29, 2026 AT 12:15 PM

Imagine being a kid with epilepsy and your mom has to pay $800 for a liquid version of a drug that’s been off-patent for years… because some suit in a suit got a six-month extension by doing a study on 37 children. Meanwhile, the company’s CEO bought a private island. This isn’t medicine. It’s a Shakespearean tragedy with a corporate sponsorship. 🎭💸

Marie-Pier D.

January 24, 2026 AT 09:38 AM

This is actually kind of beautiful-kids finally getting safer meds because of a loophole that big pharma can’t ignore. 🙌 I remember my cousin almost getting dosed wrong with an adult pill because there was no pediatric data. This system? It saved lives. Even if it’s also a cash cow.