Every year, millions of Americans face a brutal choice: pay for their medicine or pay for rent. It’s not a hypothetical. It’s real. A woman in Ohio skips her insulin doses every other day because her co-pay is $400 a month. A veteran in Texas cuts his heart medication in half to make it last. These aren’t outliers-they’re symptoms of a broken system. The U.S. spends more on prescription drugs than any other country in the world, yet Americans don’t get better outcomes. They just pay more.

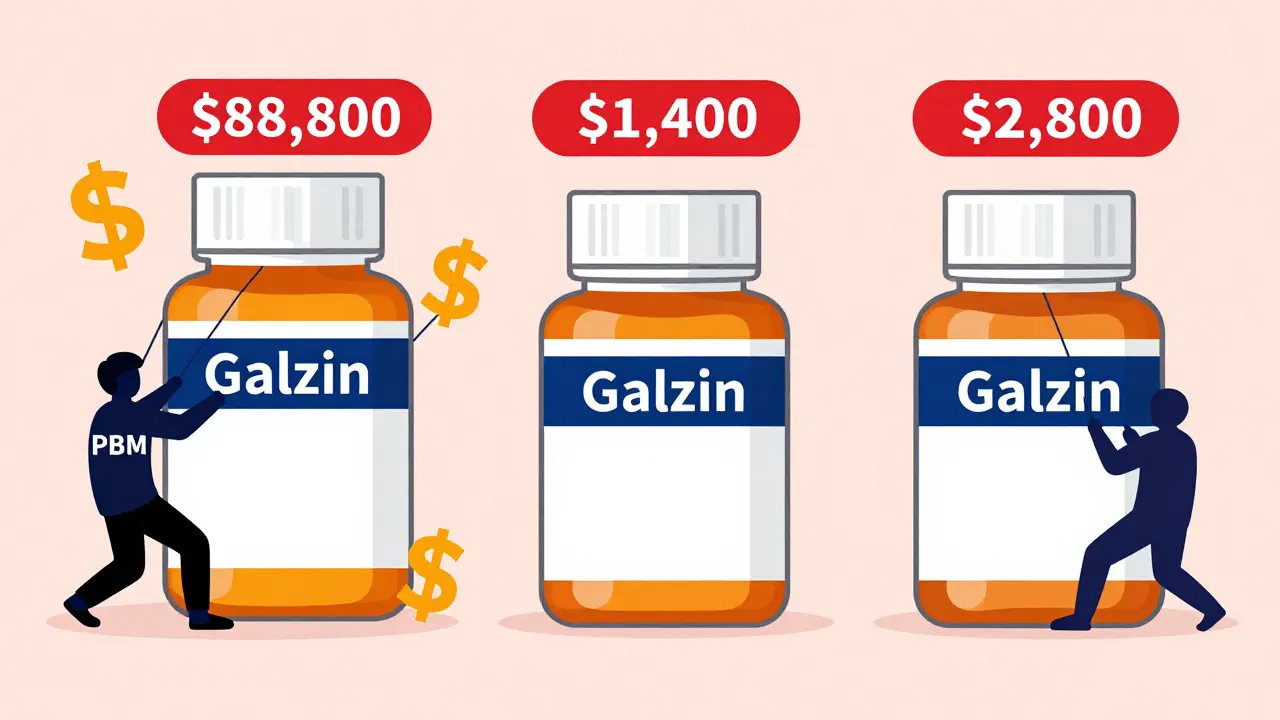

The Same Pill, Three Times the Price

Take Galzin, a drug used to treat Wilson’s disease. In the United States, it costs $88,800 a year. In the United Kingdom? $1,400. In Germany? $2,800. That’s not a mistake. It’s not a pricing error. It’s the norm. The exact same pill, made in the same factory, shipped in the same box, sold at a markup of over 1,500% just because it’s sold in America. This isn’t rare. The White House confirmed in November 2025 that Americans pay more than three times what people in other developed countries pay for the same brand-name drugs-even after factoring in manufacturer discounts. And it’s not just old drugs. The newest treatments for obesity and diabetes, like Ozempic and Wegovy, were priced at over $1,000 a month in 2024. By late 2025, after five deals announced by the White House, those same drugs dropped to $350 a month. That’s a win. But it’s also proof that those prices weren’t based on cost-they were based on what the market would bear.Why Can’t the Government Negotiate?

Here’s the thing: in nearly every other developed country, the government sits down with drugmakers and says, “This is what we’ll pay.” Canada, Germany, France-they all negotiate. The U.S. doesn’t. Not for Medicare, not for Medicaid, not for most public programs. The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 made it illegal for Medicare to negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers. That law was passed with bipartisan support. At the time, the argument was that private insurers would handle the negotiating. But that didn’t happen. Instead, a new layer of middlemen stepped in: Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. PBMs were supposed to be the good guys. They were hired by insurers to get discounts. But over time, they became powerful players in their own right. Many now own pharmacies, manage insurance plans, and even have stakes in drug manufacturers. Their business model? The higher the list price of a drug, the bigger the rebate they get. So they push for higher prices-even if it means patients pay more out of pocket. It’s a system designed to reward complexity, not affordability.Who’s Really Making Money?

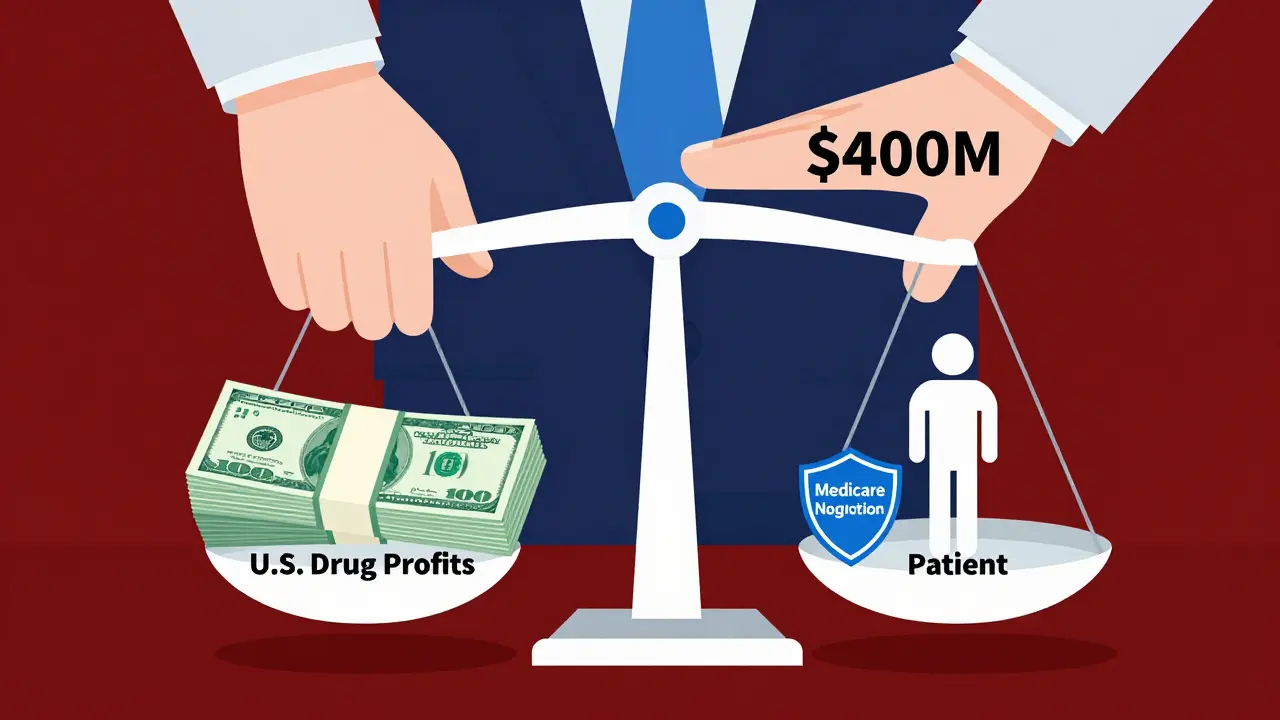

The pharmaceutical industry claims high prices are needed to pay for research and development. That sounds fair-until you look at the numbers. The U.S. has less than 5% of the world’s population. But according to the White House, it accounts for 75% of global pharmaceutical profits. That means the rest of the world is effectively subsidizing American drug prices. Drug companies make more money from U.S. sales than from every other country combined. And it’s not just the big names. Even small biotech firms with single drugs on the market can charge tens of thousands of dollars a year. Why? Because they own the patent. And in the U.S., patent protections are long, broad, and easy to extend-sometimes through minor tweaks to a drug’s formula just before the patent expires. This is called “evergreening.” It’s legal. It’s common. And it keeps prices high.

What’s Changed? Not Much

There have been attempts to fix this. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was supposed to be the turning point. It gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for a small number of high-cost drugs. In 2026, that list includes 10 drugs. That’s it. And even that power was weakened by the 2025 budget reconciliation bill, which experts say will cost Medicare at least $5 billion more than originally projected. The Act also introduced a rule: if a drug’s price rises faster than inflation, the manufacturer must pay a rebate to Medicare. That saved money on 64 drugs in early 2025. But it doesn’t stop companies from raising prices before the cap kicks in. And it doesn’t help people who don’t have Medicare. Meanwhile, the White House announced five new deals with drugmakers in late 2025, claiming they brought prices “in line with other nations.” Ozempic dropped from $1,000 to $350. Wegovy followed suit. But these are voluntary deals. No law requires them. The companies could raise prices again tomorrow. And they have. Senator Bernie Sanders’ September 2025 report found that 688 prescription drugs increased in price since President Trump took office-even after he publicly promised to lower costs. That’s not a glitch. That’s the system working as designed.Who Gets Hurt?

The people paying the most aren’t the insurance companies. They’re the patients. In 2025, 1.5 million Medicare beneficiaries were paying more than $2,000 out of pocket for their prescriptions. That’s before the new $2,000 annual cap under the Inflation Reduction Act kicks in fully. For many, that cap is life-changing. But for others, it’s too little, too late. Patients with cancer, rare diseases, or endocrine disorders are hit hardest. These are called “specialty drugs.” They make up less than 2% of prescriptions but over 50% of drug spending. In 2024, IQVIA reported that specialty drugs drove an 11.4% spike in U.S. drug spending. And that trend is accelerating. A growing number of people are rationing their meds. Skipping doses. Cutting pills in half. Going without. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) says this isn’t just a financial problem-it’s a public health crisis.

What’s Next?

There’s no easy fix. The system is built on layers of profit, legal loopholes, and powerful lobbying. Drugmakers spent over $400 million on lobbying in 2024 alone. That’s more than any other industry. Some proposals are gaining traction. Senator Sanders’ Prescription Drug Price Relief Act would tie U.S. prices to those in other major countries. It’s simple. It’s direct. And it’s blocked by the same interests that benefit from the current system. Others want to break up PBMs or force full price transparency. The HHS announced in September 2025 that new rules requiring real-time drug pricing information will be rolled out in 2026. That could help patients compare prices before they fill a prescription. But without price controls, it’s just a flashlight in a dark room. The truth is, the U.S. could fix this tomorrow if it chose to. It could let Medicare negotiate. It could cap prices based on international benchmarks. It could ban rebate systems that reward high list prices. But political will is the missing ingredient. For now, the system stays the same. And Americans keep paying the price.What You Can Do

If you’re paying high prices, you’re not powerless.- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices across pharmacies. Sometimes the cash price is lower than your insurance co-pay.

- Ask your doctor about generic alternatives. Many brand-name drugs have cheaper, equally effective generics.

- Check if your drug is on the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy list. You might qualify for extra help.

- Call your drugmaker. Many have patient assistance programs that offer free or discounted meds if you meet income requirements.

12 Comments

Kitty Price

December 17, 2025 AT 00:07 AM

My mom skipped her blood pressure meds last year because she couldn’t afford it. 😔 She’s fine now, but I still get sick thinking about it. We need real change, not just ‘voluntary’ deals that vanish when the next CEO takes over.

Also, why is it so hard to just say ‘prices should be fair’? 🤷♀️

Colleen Bigelow

December 18, 2025 AT 01:08 AM

THIS IS A GLOBALIST SCHEME. The WHO and Big Pharma are working with the UN to destroy American sovereignty. Why do you think they let Canada and Germany pay less? Because they want us weak. They want us dependent. They want us begging for handouts while they ship our pills overseas and sell them back to us at 10x.

And don’t get me started on PBMs-they’re the real enemy. They’re not even American companies anymore. Half of them are owned by Chinese and Saudi investors. You think that’s a coincidence? It’s not. It’s deliberate.

We need to ban all foreign ownership of drug companies. And we need to burn the Medicare Modernization Act to the ground. This isn’t capitalism-it’s treason.

Billy Poling

December 18, 2025 AT 10:23 AM

It is important to recognize that the structural inefficiencies inherent within the pharmaceutical supply chain are not merely a product of corporate greed, but rather a complex interplay of regulatory capture, intellectual property law, and the unintended consequences of market-based pricing mechanisms that were originally designed to incentivize innovation. The absence of centralized price negotiation, coupled with the proliferation of intermediary entities such as Pharmacy Benefit Managers who operate under a rebate-based compensation model, has created a perverse incentive structure wherein higher list prices directly correlate with increased profitability for non-manufacturing stakeholders. Furthermore, the legal framework surrounding patent extension-commonly referred to as ‘evergreening’-while technically permissible under current statutory interpretation, fundamentally undermines the original intent of patent law, which was to balance innovation with public access. Until Congress revises the Medicare Modernization Act to permit direct negotiation and eliminates the rebate structure that rewards inflated pricing, any incremental policy changes will remain superficial and insufficient to address the systemic nature of this crisis.

sue spark

December 19, 2025 AT 12:21 PM

My sister got her cancer drug for $50 a month through a patient program. She didn’t even know it existed until her pharmacist told her. There’s help out there. Just gotta ask. I wish more people knew.

And yeah the system’s broken. But we’re still breathing. That counts for something.

James Rayner

December 19, 2025 AT 20:24 PM

It’s funny… we’re told that capitalism rewards innovation, but here we are-paying 15 times more for the same pill, while the people who made it don’t even live here. The real innovation isn’t in the lab-it’s in the accounting department. They figured out how to turn human suffering into a revenue stream and call it ‘business.’

I wonder what Jesus would say about a system where a child’s life is priced at $88,000 a year… and the answer isn’t ‘let’s fix it’-it’s ‘let’s find a workaround.’

anthony epps

December 21, 2025 AT 04:34 AM

why is it so expensive? i just want to know. is it because the pills are hard to make?

Andrew Sychev

December 22, 2025 AT 00:30 AM

They’re not just overcharging-they’re murdering people slowly. This isn’t capitalism. This is a blood sport. And the people who profit from it? They sleep in mansions while grandmas choose between insulin and groceries. And you call this freedom? No. This is a war. And we’re losing.

They laugh at us. They know we’re powerless. But one day, someone’s gonna set their office on fire. And I won’t be sorry.

Dan Padgett

December 23, 2025 AT 12:11 PM

Back home in Nigeria, we get most of our meds from India. A year’s supply of insulin costs less than $20. We don’t have fancy labs or billionaire CEOs. We just have people who need to live. America has everything-science, money, power-and still, you let people die because of paperwork and profit margins.

It’s not about cost. It’s about choice. And you chose wrong.

Hadi Santoso

December 23, 2025 AT 15:55 PM

goodrx saved my life. i found a pharmacy that sold my asthma inhaler for $18 cash. insurance wanted $140. i didn’t even know this was a thing until my friend told me. also, ask your doc about generics. they’re not ‘weaker’-they’re the same damn thing.

also pbms are scum. they’re the middlemen who get rich while you skip doses. someone needs to sue the hell out of them.

Arun ana

December 24, 2025 AT 23:59 PM

My cousin in Canada pays $5 for the same drug I pay $400 for. I cried when I found out. We’re both diabetic. Same body. Same science. Different country. Different fate.

It’s not fair. And it’s not right. We need to fix this. Not someday. Now.

Kayleigh Campbell

December 25, 2025 AT 03:43 AM

So the White House ‘negotiated’ prices down to $350… and we’re supposed to clap? Like, wow, you finally stopped robbing us blind by 65%? That’s not a win. That’s just admitting you were stealing before.

Also, ‘voluntary’ deals? That’s like saying ‘I’ll stop punching you in the face… if I feel like it.’

Meanwhile, the people who actually need these drugs? Still rationing. Still dying. Still waiting for someone to care enough to fix it.

GoodRx is a bandaid on a severed artery. And we’re all pretending it’s a solution.

Ron Williams

December 16, 2025 AT 20:26 PM

Been there. My dad’s on six meds. One of ‘em went from $120 to $450 in two years. We used GoodRx to find a pharmacy that sold it for $89 cash. Crazy, right? The system’s rigged, but we’re learning to game it. Not ideal, but it keeps him alive.

Still, I don’t get how we let this happen. We’re the richest country on earth. We can do better.